“Translations from the English” ~ An Interview with Poet Jeff Schwaner (5/20/16)

Transcript (edited slightly for clarity)

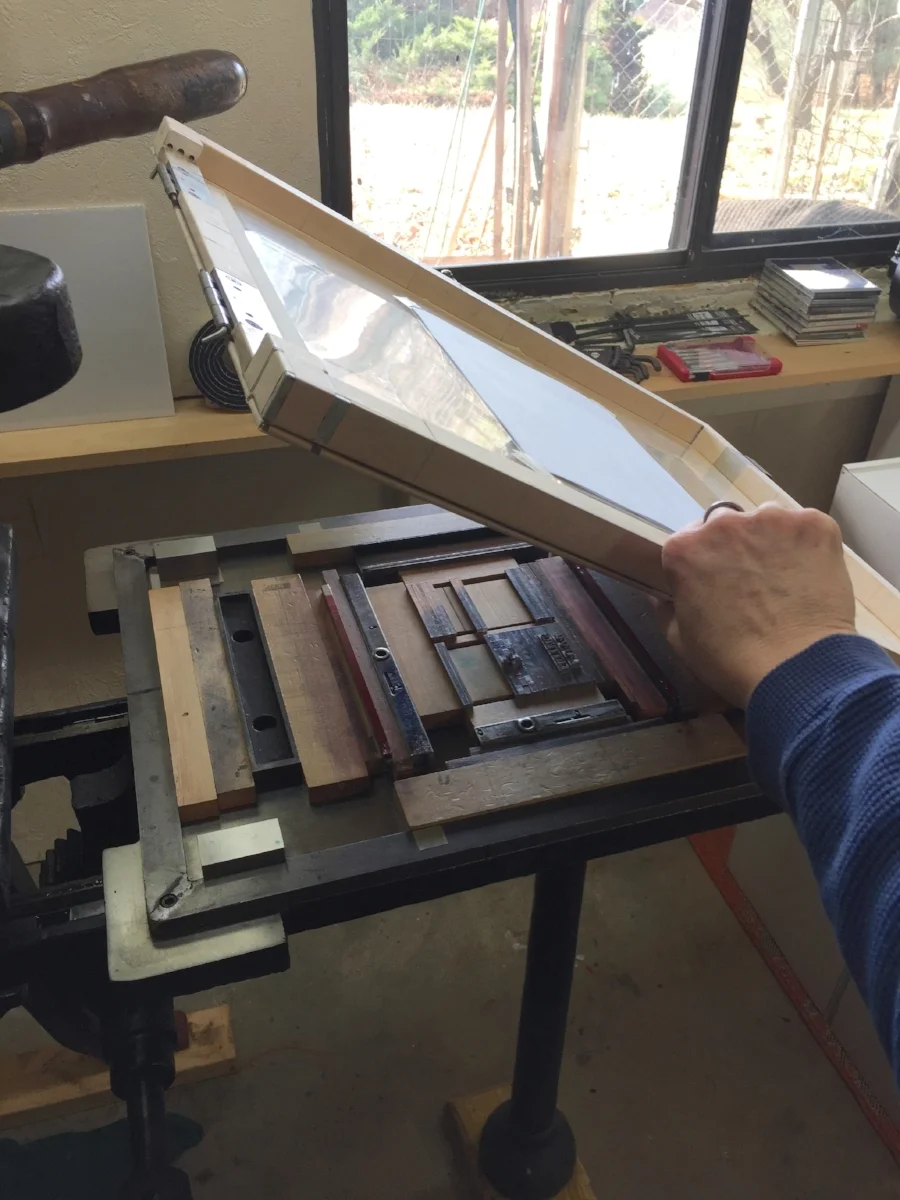

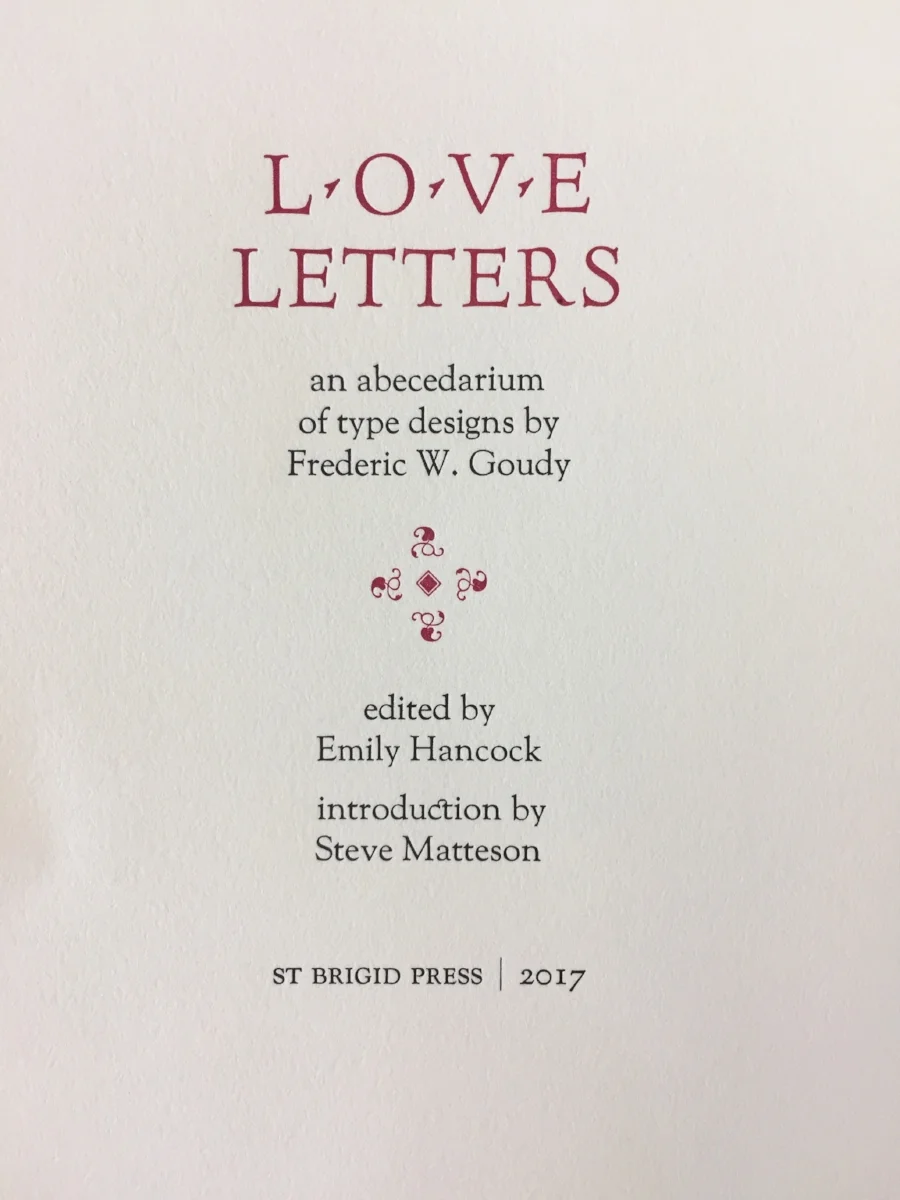

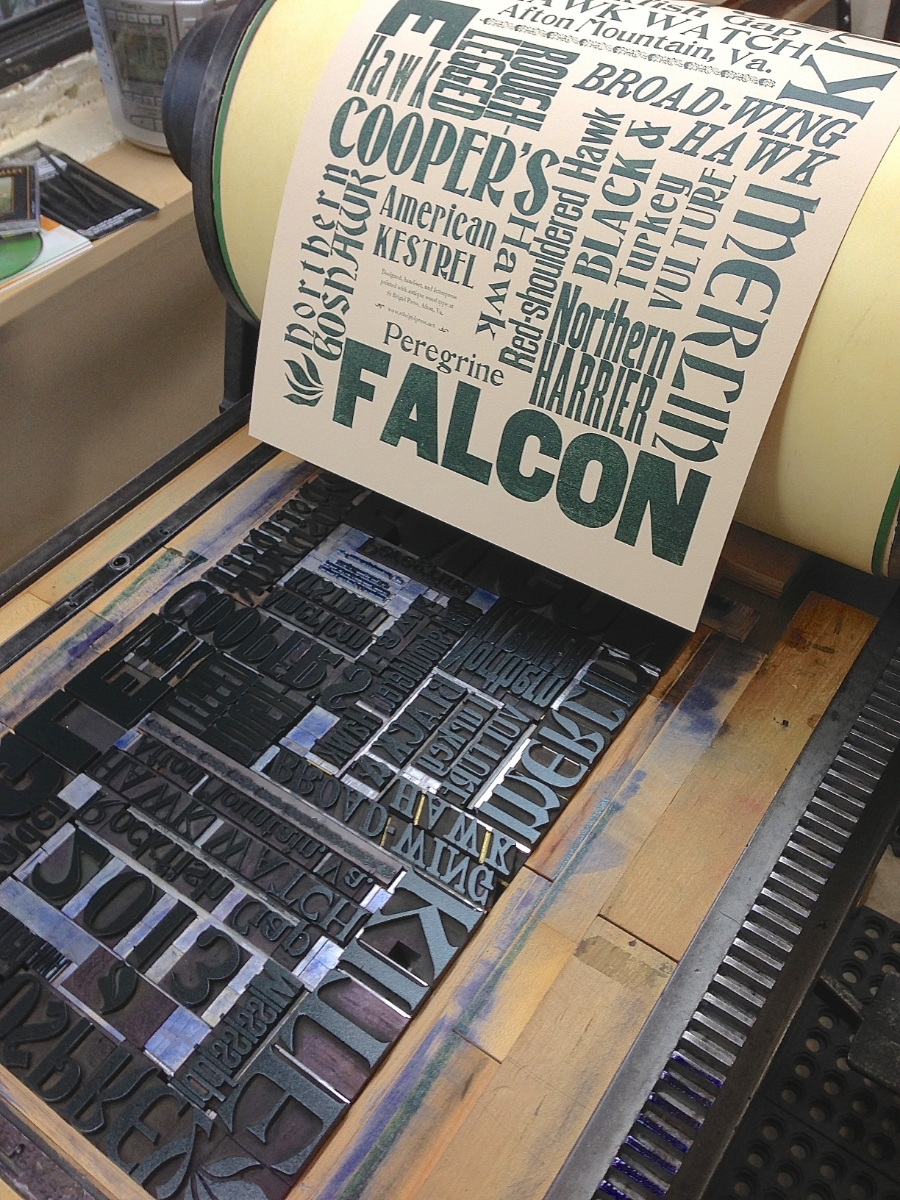

EMILY HANCOCK (EH): Hello and Welcome to “Podcasts from the Press!” This is the second in our series of live interviews with authors and artists, conducted here in the shop of St Brigid Press in Afton, Virginia. I’m your host, Emily Hancock, and we are delighted to have with us today poet Jeff Schwaner.

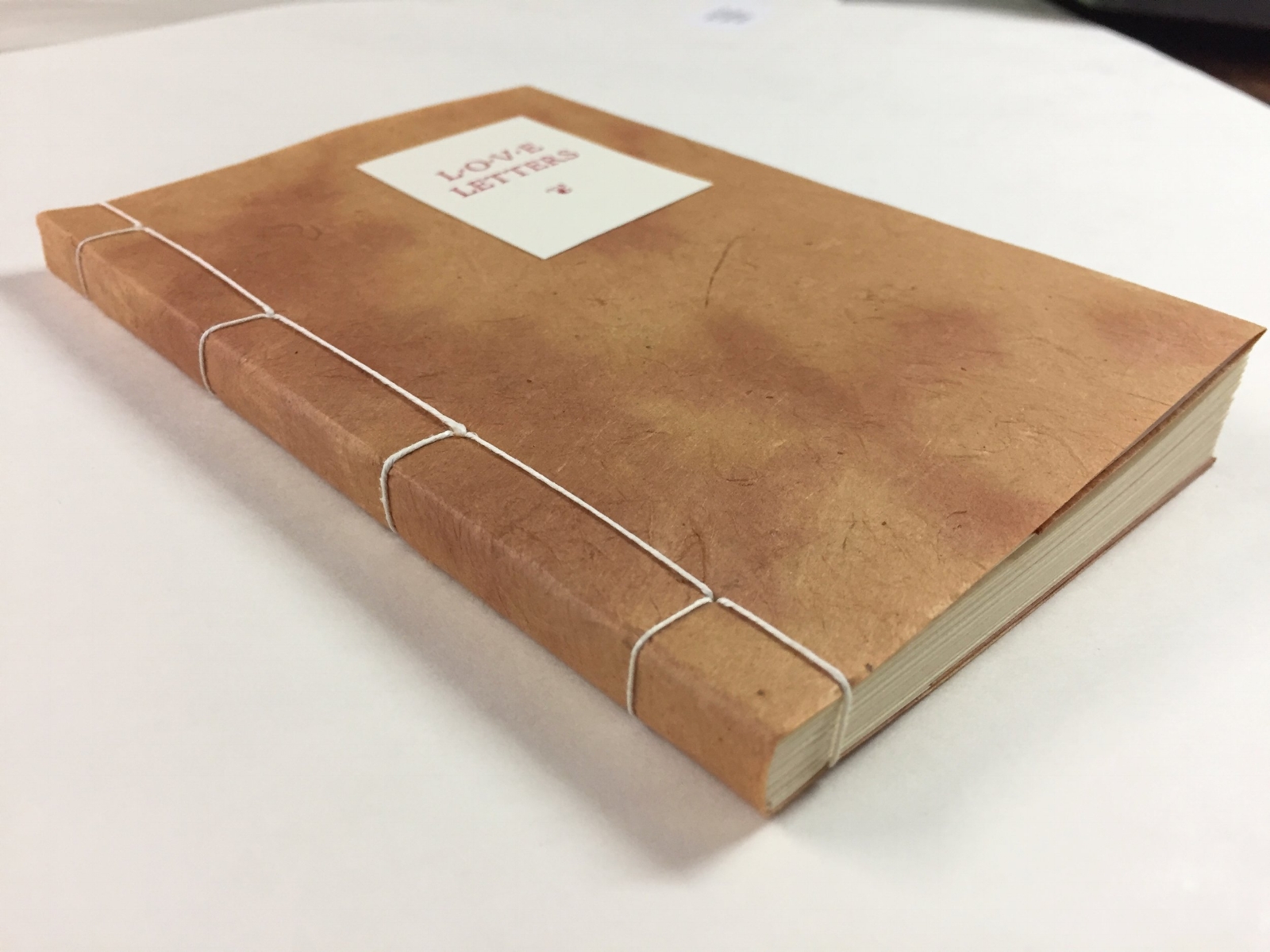

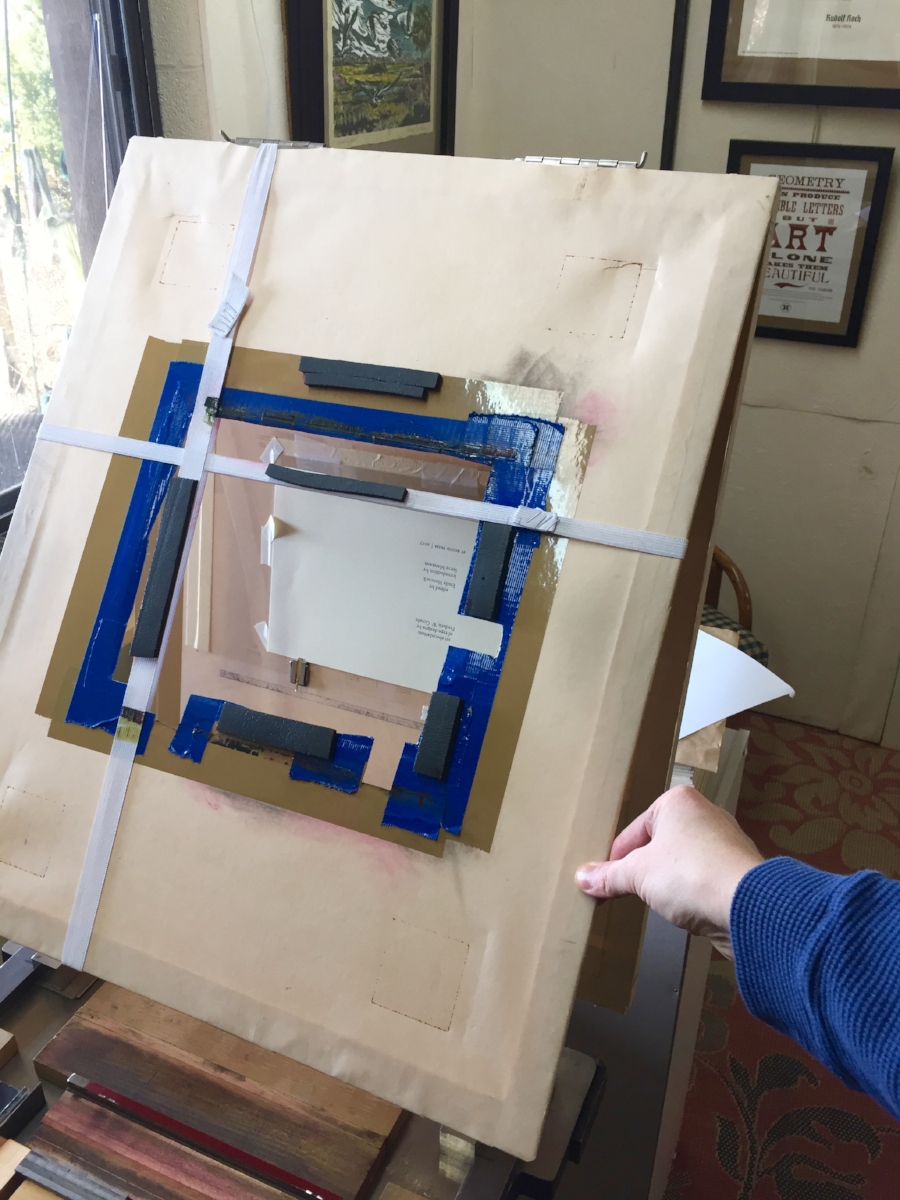

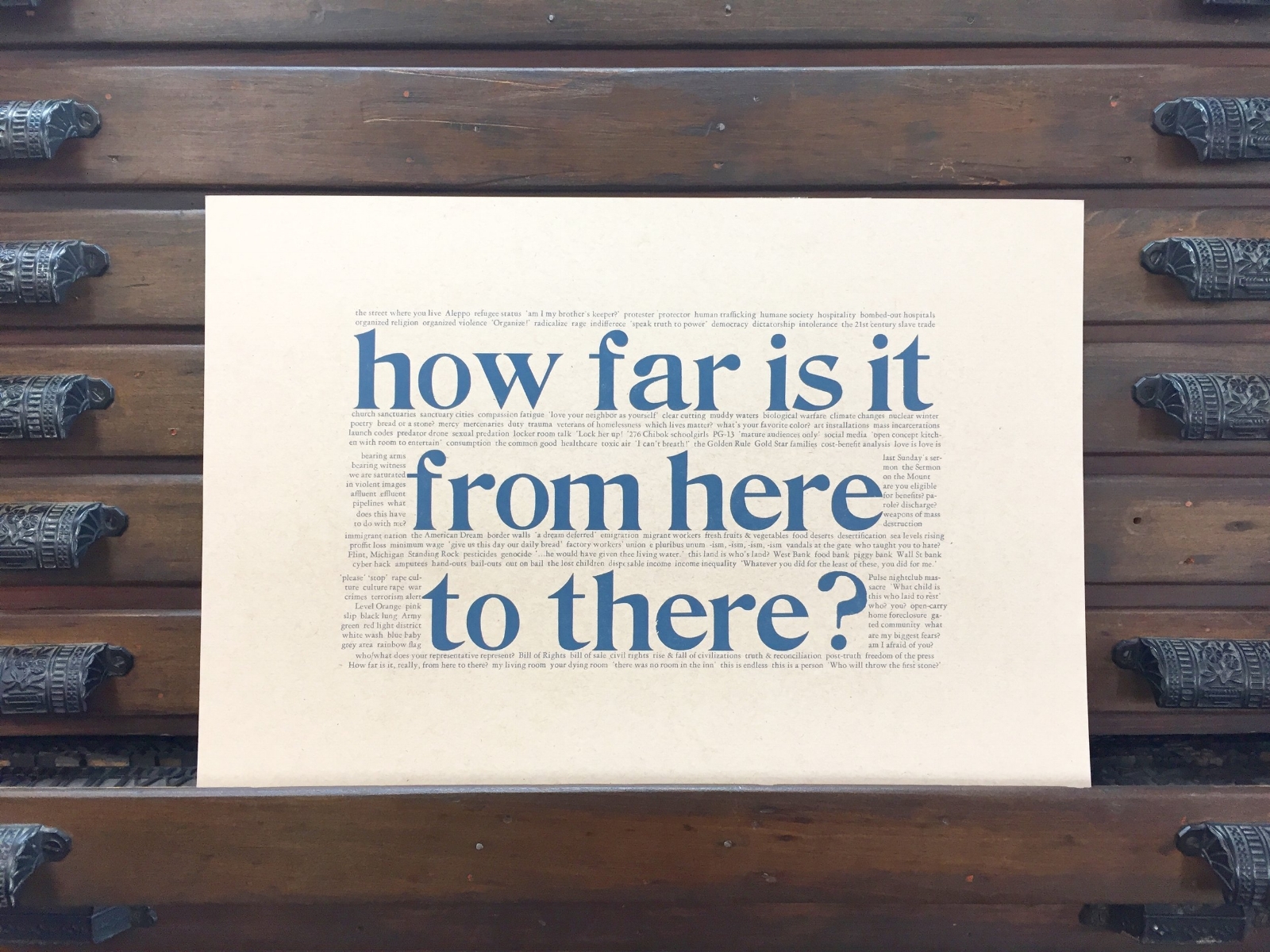

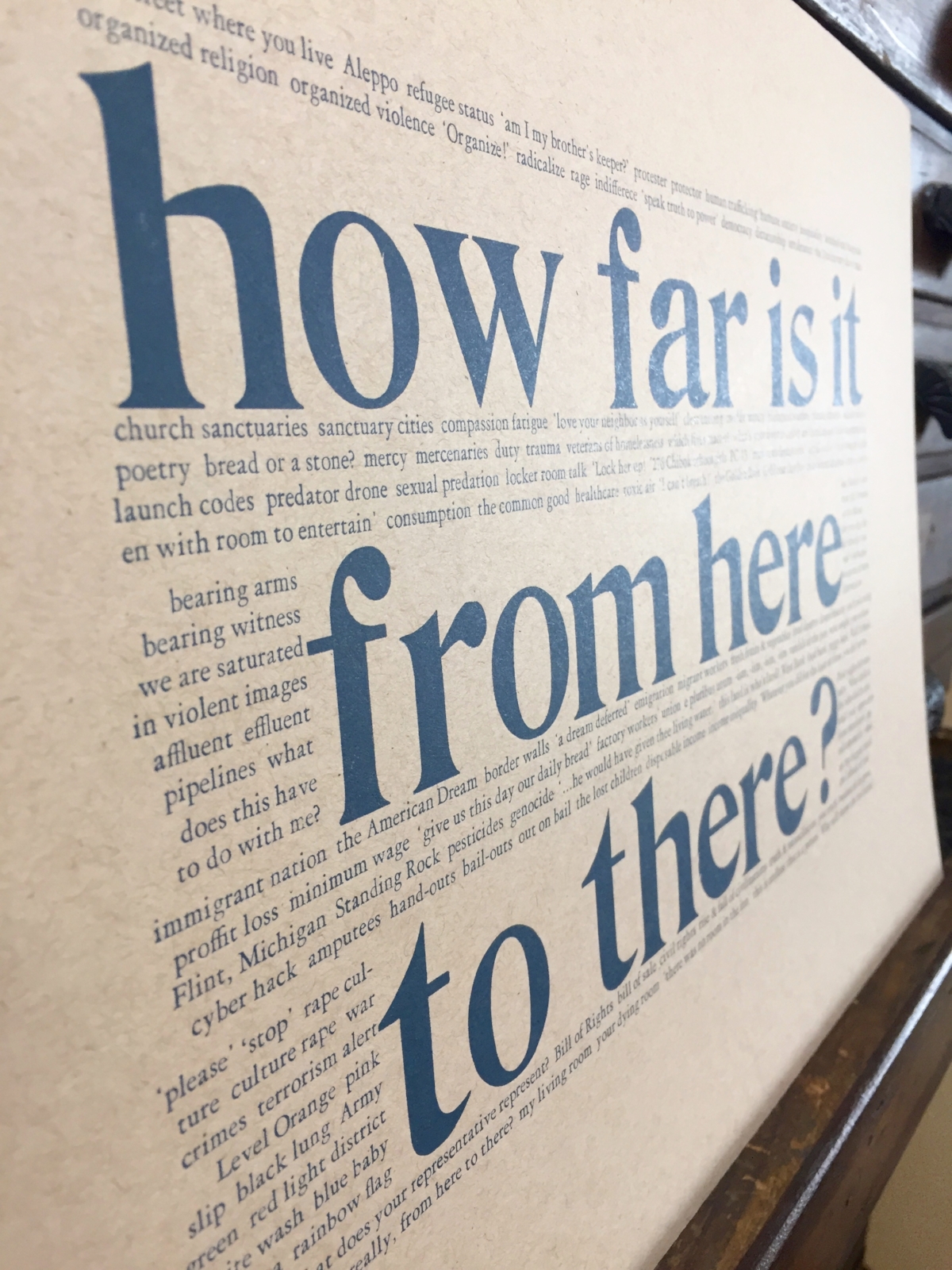

Jeff has authored five books of poems and two novels, and has had a long career in the publishing industry, from bookselling and digital publishing, to writing and editing with several newspapers. He and I have collaborated on a couple of projects so far, including a letterpress printed broadside of one of his poems, the special binding of his latest collection of poems, and a forthcoming chapbook.

Jeff, welcome back to St Brigid Press, and thank you for taking time to chat with us today!

JEFF SCHWANER (JS): I’m really happy to be here. And I have to say this is the first time I’ve been down in your print shop and not seen you covered with ink. [laughter] So, it’s unusual, might take me a while to get used to it.

EH: [laughter] I thought we’d start with one of the first things that I found out about you, when I heard that you were a poet in Staunton and went to see your website. On your website you quote the Swedish poet, Tomas Tranströmer, who says, “The one who has arrived, has a long way to go.” And your site itself is called “Translations from the English.” Can you talk a bit about both the influence of Tranströmer and the idea and action of translation in your work?

JS: Sure. I’m sure I disappoint a lot of people on a daily basis who are looking for translations from the English, of poems actually written in other languages. But I’m happy for the traffic. [laughter] But, yeah, I think it was the late ‘80s and I was fresh out of graduate school and looking for a book of poems in the Cambridge Public Library by Fernando Pessoa that Ecco Press published. The library didn’t have Pessoa, but luckily they had a book that looked eerily similar, because all those Ecco Press books looked alike, and it was a selection of poems by Tranströmer.

So I opened it up, and the first poem of his first book, the first line reads, “Waking up is a parachute jump from the dream.” So that just opened up a brand new world to me, and so I got the book and I’ve been reading Tranströmer ever since. When I was a bookseller in Charleston, South Carolina, I remember seeing that Ecco Press did a reissue of the book, and I bought ten copies with my bookseller’s discount. And I wrote in a literary journal I was publishing in the city at the time, called Captain Kidd Monthly, that if people wanted to read this great poet, just come by the bookstore and I would give them a copy. I gave away copies of the book, I loved this guy’s work so much.

What I love about Tranströmer is that, in any of his poems, you get the feeling that he recognizes — and he’s a trained psychologist, and he worked with troubled kids in youth prisons, as a career — that he understands that much of our experience takes place in an interior landscape. But that the most mindful way to access that seems to be through the external landscape. So there’s a lot of natural details, and a lot of weather, a lot of things like that in his poems. He writes in a lot of images that are really strong. And because his poetry does not rely on the specific nuances of his native tongue, then I found from reading five, six, even more translations of the same poem that, even though the translations could vary and you could argue, “Well, Robert Bly’s translation, you know, pales in comparison to Robin Fulton’s translation,” or whatever (and there have been arguments about the value of different translations of his work), that the poem still comes across. When I kind of figured that out, as I got access to more translations and as I was starting to write a lot more, starting about 2010 I really said to myself, “I want to be able to write the type of poem than anybody could read in any language and they would get some of the essence of it.”

So there’s that, wanting to write something that could go through the wringer and still get across to a reader on the other side of the world, wanting to write a poem like that and also the idea that (and we all kind of know this, though it escapes us in the course of the day) that just by writing, just by using language, we’re having to translate something, that has no words, into words. So, thus Tranströmer and thus the name of this site. My poems are “translations from the English” in a certain way, because first you have the “no word” poem in your head, and then you have words that sound awesome in your head, and then you have the valuable insight of knowing that the words that sound awesome in your head don’t sound great when you say them aloud for the first time, in many cases! So you have to put it in this other medium.

EH: Absolutely. Was Tranströmer an inspiration for you to try your own hand at actually translating from a foreign-to-you language?

JS: No, I did a little bit of translation from the German when I was in college, but I never really thought about translating too much. I was a big [Bertolt] Brecht fan and a Nietzsche fan and a Goethe fan; there were a lot of great German writers that I liked in college. But as a poet I never had much interest in foreign language poetry until recently, when I came across the classical Chinese poetry of the T’ang Dynasty [618-906 CE] and the Song Dynasty [960-1279 CE].

EH: And that seems, to me, a perennial theme: Tranströmer, the ancient Chinese poets, and you — that interior-to-exterior communication, translation, weaving.

JS: Oh, yes. Tranströmer is this 20th-21st century version of what I think the Chinese did so well. [I read] Han Shan, the Cold Mountain poet, back in 2011 for the first time. I didn’t read a lot of poetry-in-translation, a lot of international poetry [until then]. I was taking a trip to New York, a business trip, and was going on the train and trying to pack light. I was in a bookstore looking for — well this is crazy because you think poets are all about quality, but I was looking for a small-sized book that would be easy to carry, and I found J.P. Seaton’s translation of Han Shan. I thought, “Ok. I can carry this around anywhere, can read it on the train.” I read it on the train, and in that 6 hour trip I was blown away. By the simplicity, and by how much can be said in a poem without saying it. And, again, these are translations of poems that are a thousand-plus years old, in the case of Han Shan.

That, in turn, turned me on to reading most of the T’ang Dynasty poets that are translated, and the Song Dynasty, which is the period of writing after that, where I met my buddy Mei Yao-ch’en. The ability to use the details of the natural world to describe an interior state is what so much of classical Chinese poetry is about. That’s really over-simplifying it, and there are many things that do not translate — cultural things, language things, that do not translate about those poems.

EH: Right. There’s the Italian phrase, “The translator is the traitor.”

JS: Yes, yes.

EH: You recently published a book of poems called Moonlight & Shadow, which engages one of the [11th century] Chinese poets, Mei Yao-ch’en, in a series of poetic conversations across time and space. So you have the interior and the exterior and that time and space — how did this book come about?

JS: Mei Yao-ch’en is considered to be one of the first poets of great quality to come out of the Song Dynasty, which is the period after the T’ang Dynasty, where you had Li Po and Tu Fu and a lot of the guys who are considered your Top Five Poets. So I was going through, with great vigor, this poetry and really enjoying it, and I got to Mei Yao-ch’en and there was something about a generosity of spirit in this guy that really struck me.

I’d been experimenting for a while in my writing with what I call unregulated verse — it’s a form that’s not quite a form, but it’s based in part on the regulated verse of those classical Chinese poets. There’s really no way to translate the form, but there are certain themes that I keep in mind, certain rules that I adhere to. There’s no beat-count, but basically it’s written in couplets and I try and adhere to certain rules. And one of those rules is not to get too talkative, right? [laughter] Many of these poems of regulated verse are four-line poems, are eight-line poems. Sometimes they can go on-and-on, but for the most part those were some of the basic forms that were collected and anthologized by the Chinese of these [eras].

So, I was working in that form anyway, and Mei Yao-ch’en just spoke to me in a way that very few writers do. Melville speaks to me that way; there’s a real generosity of spirit in Melville that you see in Moby Dick and all his other stuff, too. When I was reading Mei Yao-ch’en I got a great feeling of that. Can I read one of his poems?

EH: I would love for you to.

JS: This is a David Hinton translation. [Mei] is not translated widely, but I’ve read as many translations of his work as I can find. And I’ve actually tried to translate a couple of poems by him. This [poem of his] is called “Lunar Eclipse.” One thing to know is that in the 11th century, when Mei Yao-ch’en was alive, the eclipse was considered kind of a supernatural thing. So a household might do some weird things when they see an eclipse. They might bake roundcakes, they might do all of these things to “bring the moon back.” They might bang pots and pans, stuff like that. So there’s reference to that [in this poem].

Lunar Eclipse

by Mei Yao-ch’en, translated by David Hinton

A maid comes running into the house

talking about things beyond belief,

about the sky all turned to blue glass,

the moon to a crystal of black quartz.

It rose a full ten parts round tonight,

but now it’s just a bare sliver of light.

My wife hurries off to fry roundcakes,

and my son starts banging on mirrors:

it’s awfully shallow thinking, I know,

but that urge to restore is beautiful.

The night deepens. The moon emerges,

then goes on shepherding stars west.

JS: The other cool thing about Mei Yao-ch’en is that he was totally unafraid to write about stuff that other people wouldn't write about. Here’s a title of one of his poems — (and Hsieh Shih-hou was a relative of his by marriage; they were relatives, but they were also friends, and [Mei] wrote a lot of poems with Hsieh Shih-hou in mind or to him) — and so this title is “Hsieh Shih-hou Says the Ancient Masters Never Wrote a Poem About Lice, and Why Don’t I Write One.” [laughter]

That’s the other really interesting thing about the poetry of this time — you might have poems, like I said, that are only four lines long or eight lines long, but these poems might have HUGE titles. It’s kind of humorous, because they really go out of their way to explain everything you need to know to understand how wonderful the poem you are about to read is going to be. And beyond that even, in the way these poems were transmitted socially, from friend to friend, there might be these huge introductions about, “We Were Out Drinkin’ on Top of a Mountain, and Then We Had Our Little Poetry Contest and Ou-yan Wrote This Poem to Which I Responded with This Poem Which I’m Now Giving This Boy to Carry to You,” and so on and so forth. [laughter]

In the Mei Yao-ch’en poems [that I wrote] I imagined that I found a way to transport Mei Yao-ch’en into the future, at the same age that I was (so 48, turning 49).

EH: And this is the collection of your poems, Moonlight & Shadow, in which you converse with Mei Yao-ch’en through the millennia.

JS: Right. Obviously, time travel has a lot to with it, in reflecting on time and thinking about time, thinking about death and mortality. Because, imagine that you were thrust a thousand years into the future and your wife was dead and your friends were dead, and you were still alive and you kind of saw your place in history or lack of a place in history, and at the same time trying to keep in mind to enjoy the place that you’re in, discover things, in that kind of way that I think Mei Yao-ch’en had in dealing with the difficulties in his own life.

Okay to read a poem from [Moonlight & Shadow] now?

EH: Please read a poem!

JS: This is from the middle of the book, [which] is a year long. This guy [Mei] kind of bunked with me for a year, and everything I did I thought about hanging out with Mei Yao-ch’en while I was doing it. How an 11th century poet with an open mind might respond to the difference in things. So, the very first poem was about overhead lighting. There’s a beautiful poem that Mei Yao-ch’en writes: his wife and his first son died in the matter of a couple months when he was in his late 30s or early 40s, and he writes a poem after that about being with his other two children, and going out to some event or celebration town and he sees lots of couples walking and he misses his wife. He goes home, his kids come in to see how he’s doing, and he moves the lamp because he doesn’t want them to see his face. It made me think, “Man, you cannot move the lamp today! You just can’t, because there’s overhead lighting!” The way that our entire communities are lit is different. Thinking about little things like this. You don’t get wildlife coming around, it interrupts the hunting of your basic owl on the other side of the window, etc. So, I’m putting Mei in situations where he can kind of consider those things in a philosophical way and write.

In this case, it has to do with pizza and Guinness and folklore about peonies. Again, it’s not a long poem, but the title is probably even longer.

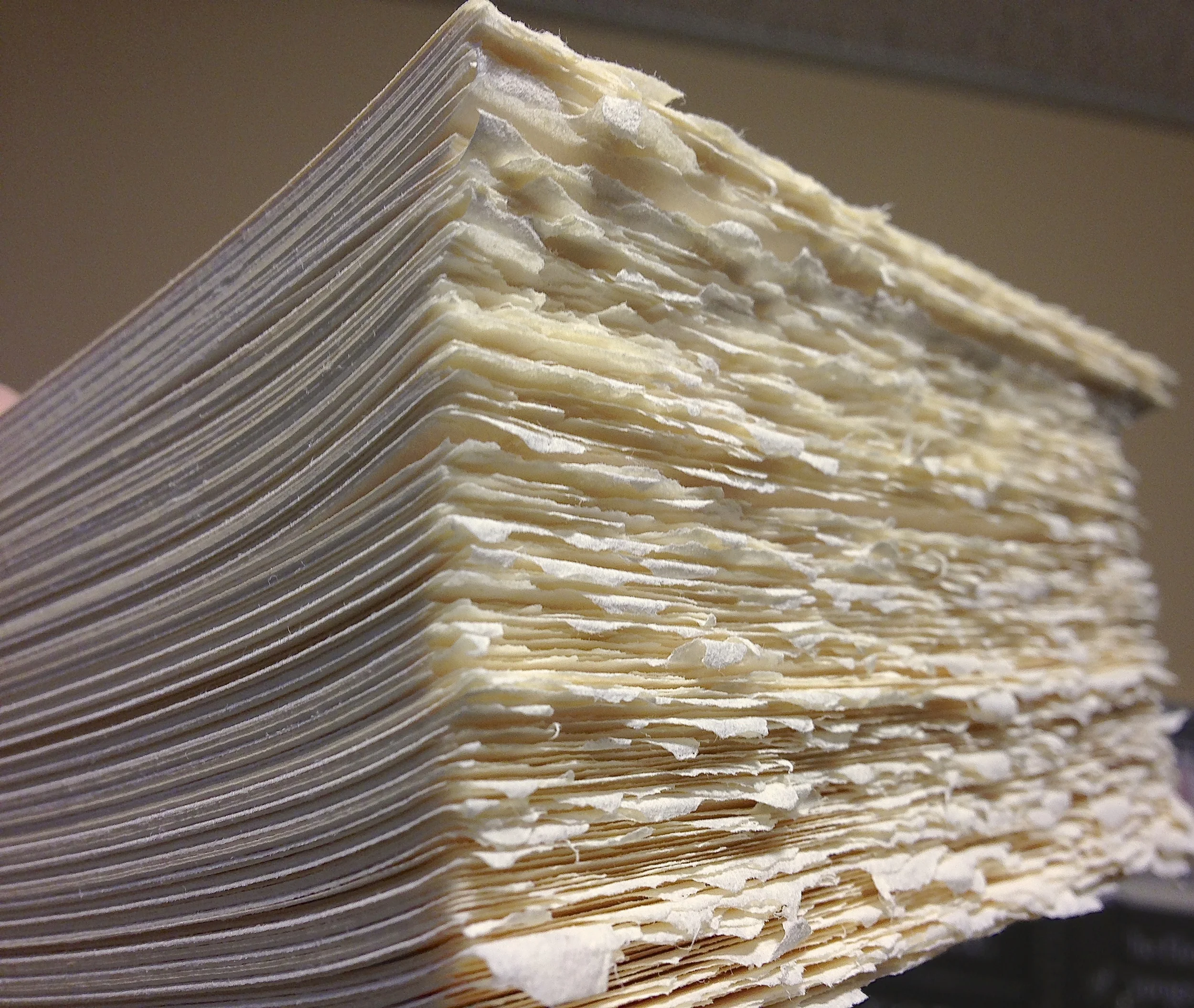

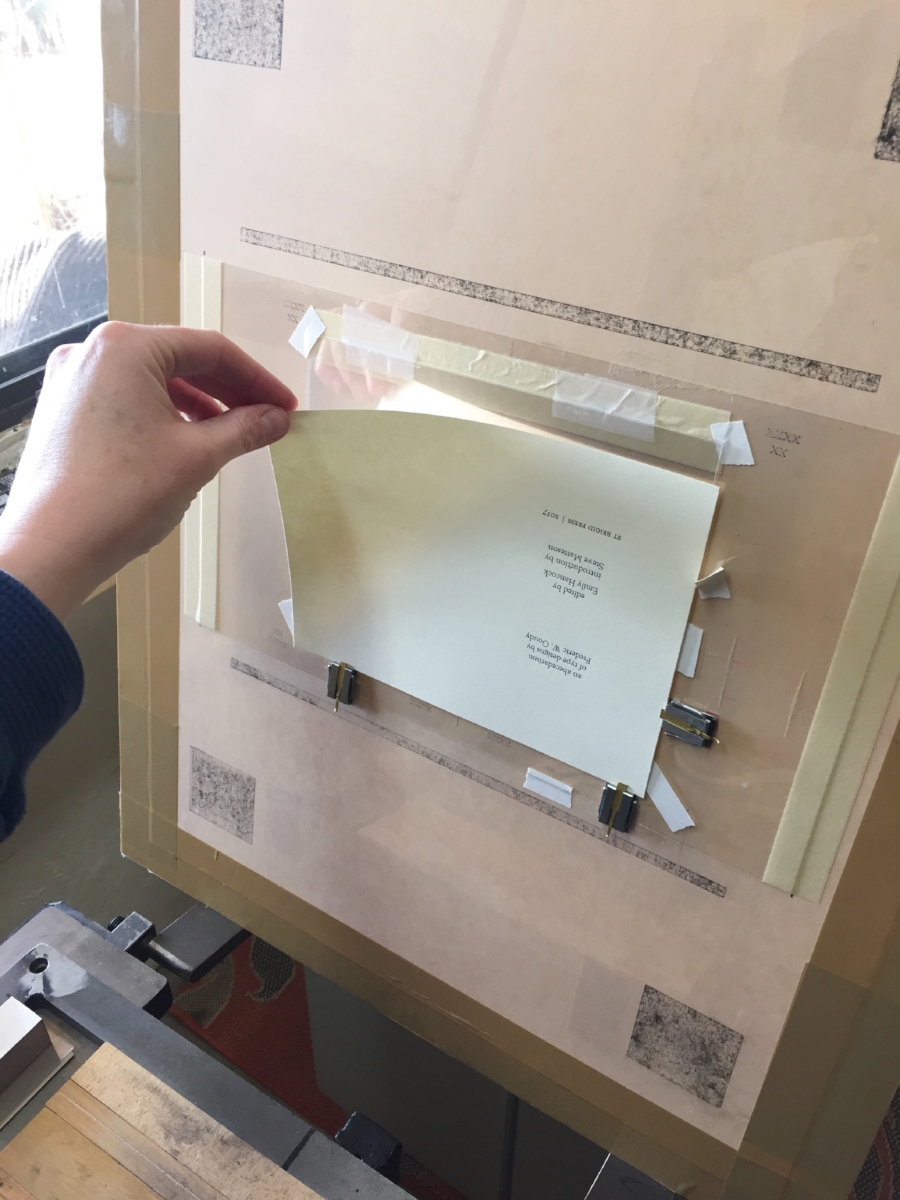

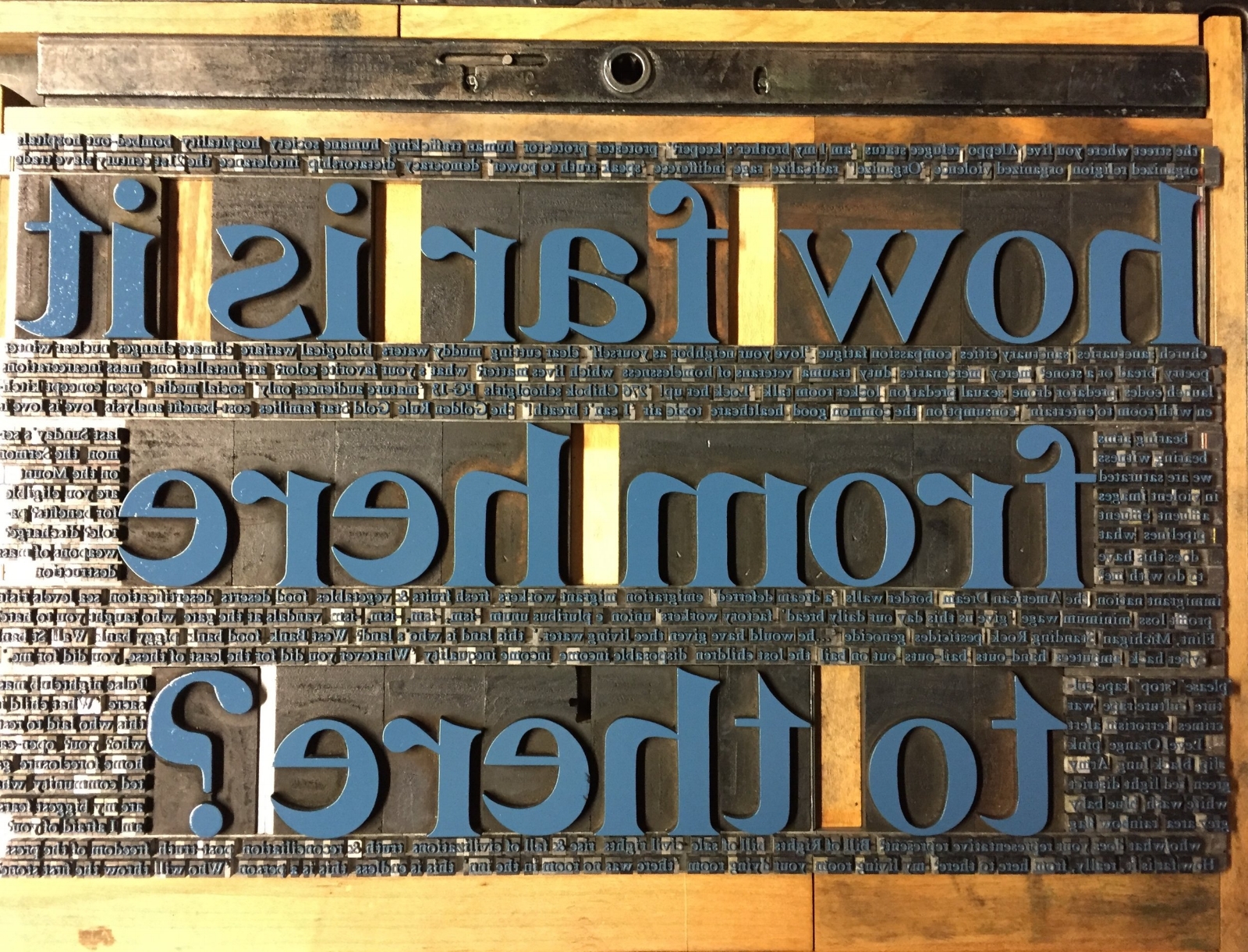

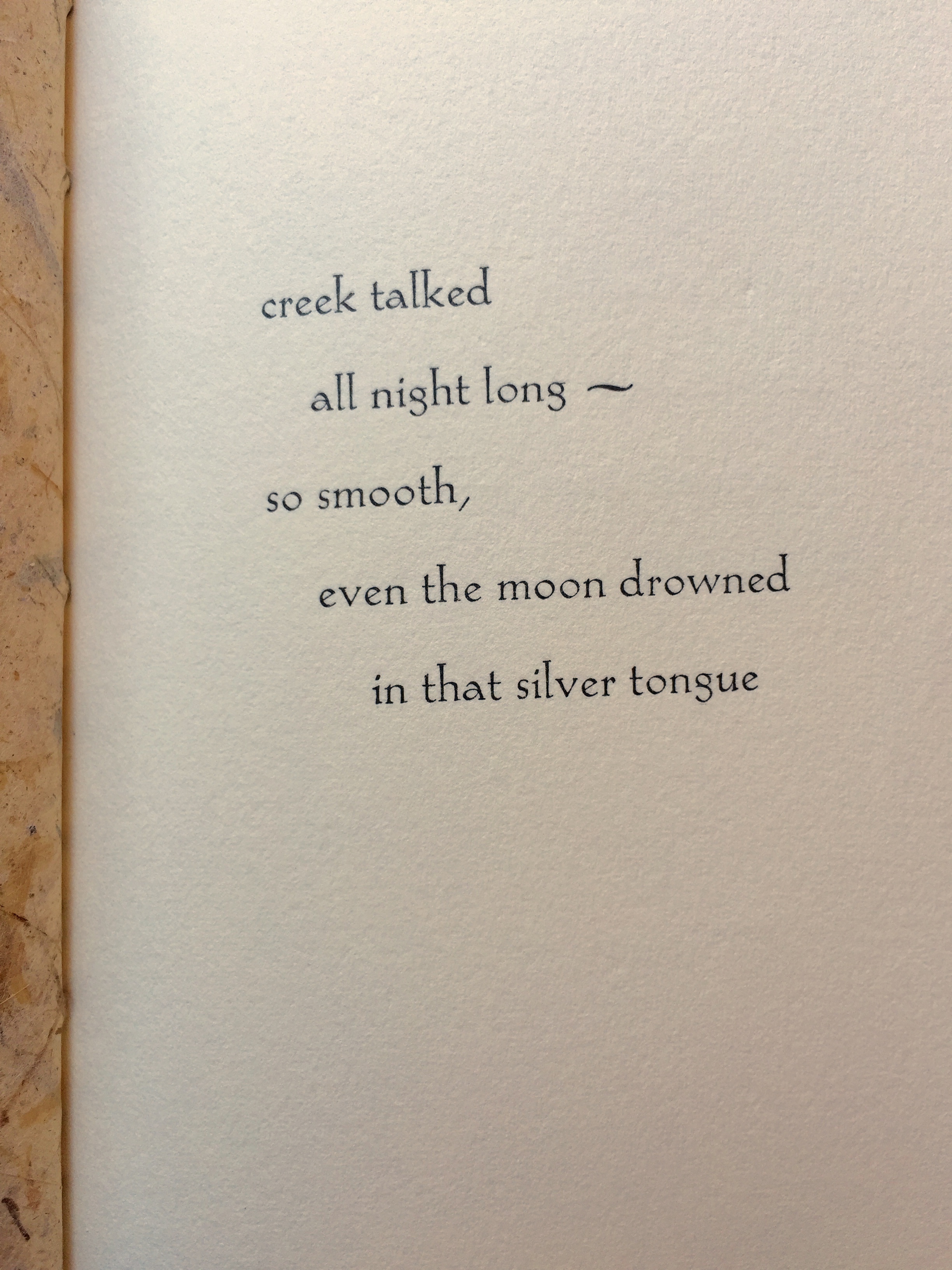

EH: I just have to say a word about the format of your book, Moonlight & Shadow. I’m looking at the page here, from which you are about to read, and the size is something like 12 [inches] by 14 [inches], a large-format book, and the title takes up fully half the page. Then there’s a wonderful little decorative line, then the poem at the bottom of the page.

JS: Yes, it’s 11x14 size page, and you know it’s a really big book because you bound it [at St Brigid Press] and made these beautiful book-boards for it. The titles are in big capital letters. I wanted to kind of reflect the way that poetry would be written out, in these kind of banners. So the title itself is taking the place of those big Chinese characters, which are kind of inscrutable at first; you look at that title and it’s just a bunch of big capital letters, and then the poem beneath it, separated by some kind of line. Sometimes the title is much larger than the poem. There’s a little balance on this one. So I’ll read this:

Mei Yao-ch’en and I, Walking Downtown for Pizza On a May Afternoon and Counting Ourselves Lucky to Do So, Encounter a Garden Full of Budding Peonies, Nodding Their Round Heads in Agreement, Which On Closer Examination Are Each Hosting at Least One Ant, Which Leads to a Discussion of Peony Folklore over Guinness, and the Eventual Authorship of These Lines by a Certain Sung Dynasty Poet Living in My House

An ant crawls across the crown of the king of flowers.

It may be just an old wives’ tale after all

that this least artistic insect opens the peony by nibbling away at the closed bud

until its thousand petals unclose and cluster as if embracing memory

In Luoyang the peony crawls across the second largest city in the world

and opens up the city’s memory that it is beautiful in spring

And in much the same way, I nibble on these lines because I like them

having no idea what will unfold in you

If love could embrace you forever you would feel the red peony around you

If lost you were ushered home by the moon it would smile like the white peony

The dewy eyes of the first glance of your first child

are a black peony and the ants scrambling away invisibly are every moment

you lived before that moment

EH: That is beautiful, Jeff.

JS: Thank you. It was a really cool and strange experience to spend a year writing as another person, and having to respect the fact that that was a real person. Those poems are kind of their own genre, because I did not write them from my own point of view, but from the point of view of somebody I was getting to know by reading his poems in multiple translations, and trying to translate some of his poetry myself. One of those poems [of Mei Yao-ch’en’s that I translated] is kind of chucked in the back of Moonlight & Shadow, just as an homage to him.

It was a really neat experience. And one of the great things about writing that book and putting it together — [a local group of writers] meet every month at a bookstore here (Black Swan Books), and sometimes some of us go drinking beforehand and some of us go drinking afterward [laugher]. I usually have a glass of wine beforehand, as the Chinese poets did. And as I was writing this whole sequence, I was reading a lot of them to the folks at that writers’ group, and you were there for many of those. It was really neat just to see on other people’s faces as you’re reading it, how that character was developing for them, as well as for me as I was writing.

EH: The whole project blew our minds. It was an arc — you had a beginning of this connection with Mei, and then 38 poems, and then he went back to his time and place.

JS: Yes. And there are a lot of wonderful things I was able to learn by having that kind of encounter. With a lot of writing from that time period, and with biographical material about him. But also realizing that you can try and be true to a character but, any character, whether we’re reading a contemporary of ours and we think we really love the poetry and we enjoy it, we’re still making up who that poet is in our head.

EH: Yes. That’s part of the translation, even from the English. [laugher] So, you have been a word-worker for many many years. One thing that we connected about is your history with letterpress printing at Cornell. How did you get involved with that?

JS: At Cornell there’s a really cool fine arts dormitory called Risley Residential College, and I stayed there all four years. It looks like a building that was just torn out of Oxford; in fact the dining hall is based on St John’s Church, or something like that. It’s a really cool building, with towers and turrets and strange rooms and nooks and crannies and secret passages and a basement and a sub-basement. In the basement and sub-basement, there are tons of practice rooms for musicians. There was, in my time, a fully outfitted armory. There was a guy who worked there who built plate mail and chainmail armor, for people to beat each other up with and stuff. [laughter] It was beautiful, it was artwork; museums bought his stuff, and people bought his stuff to wear to Society of Creative Anachronism festivals and beat each other up, with swords and shields.

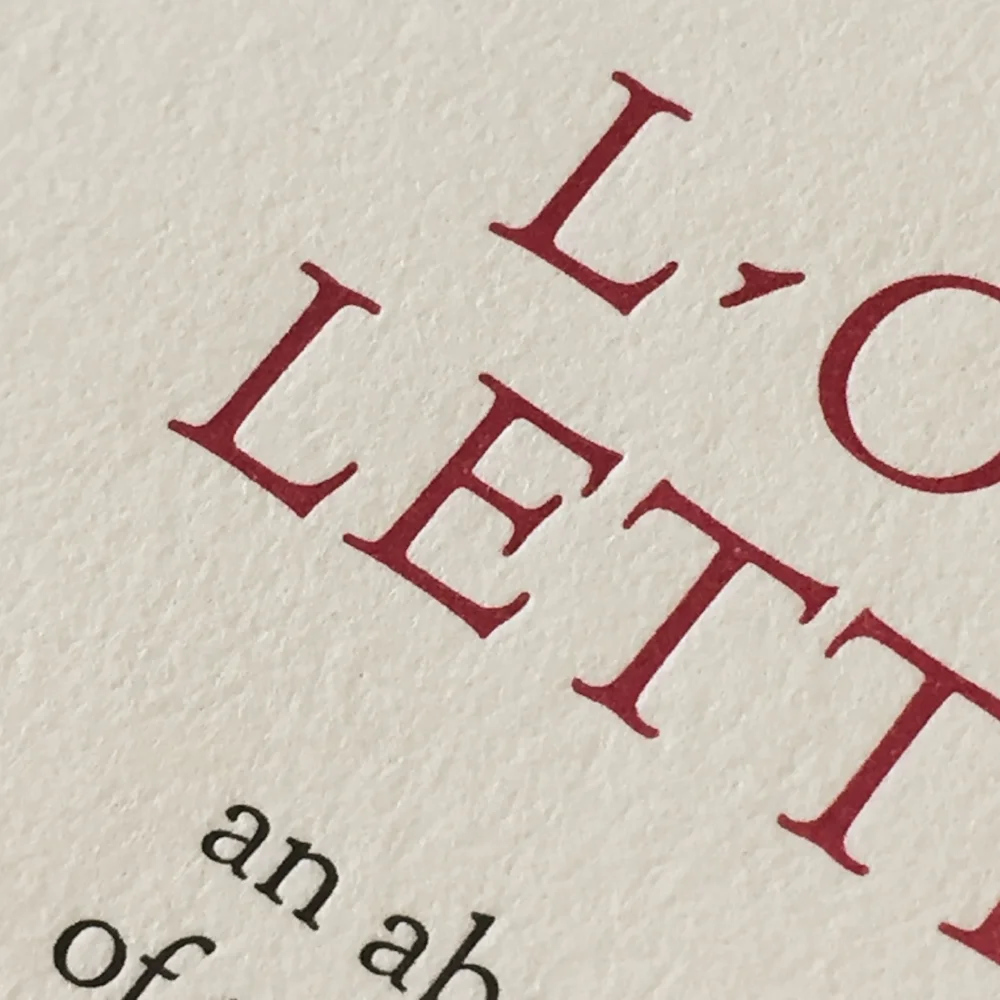

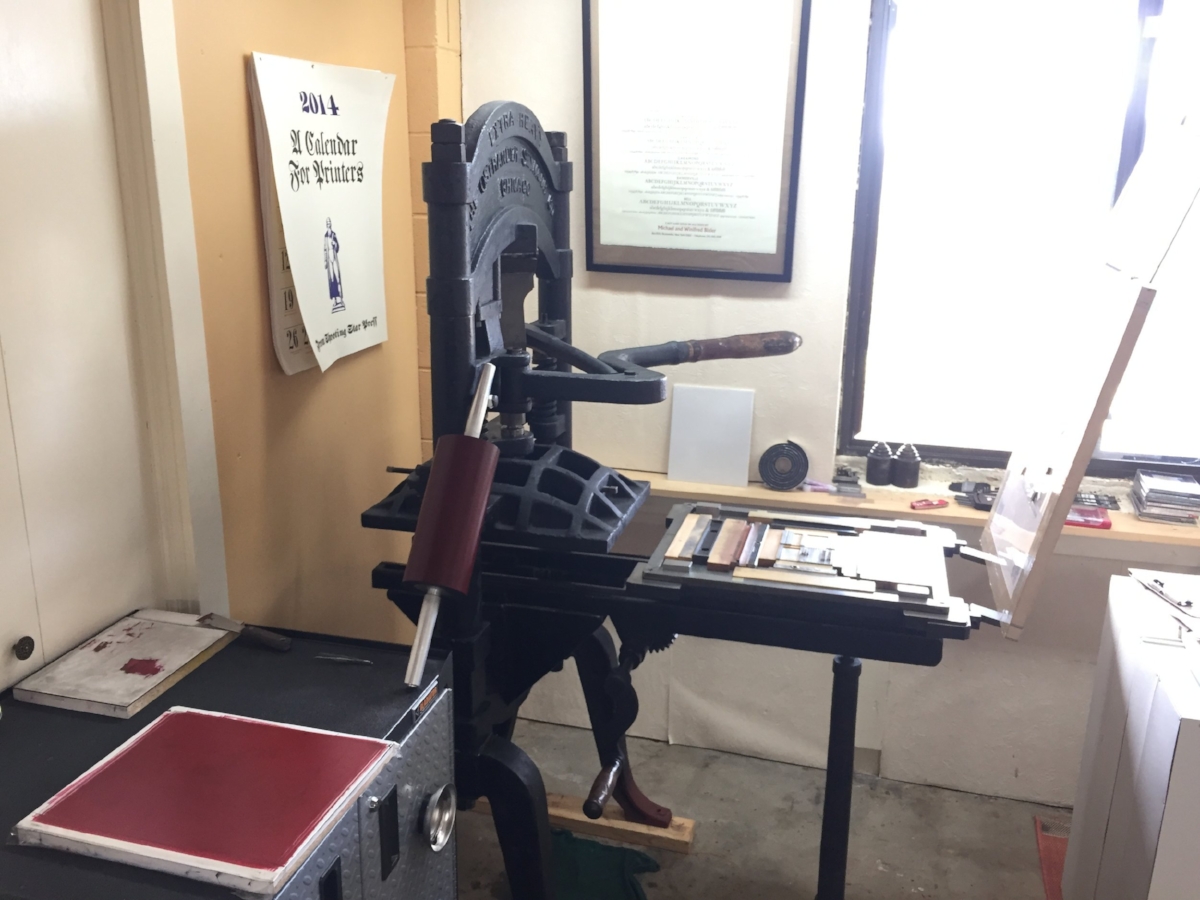

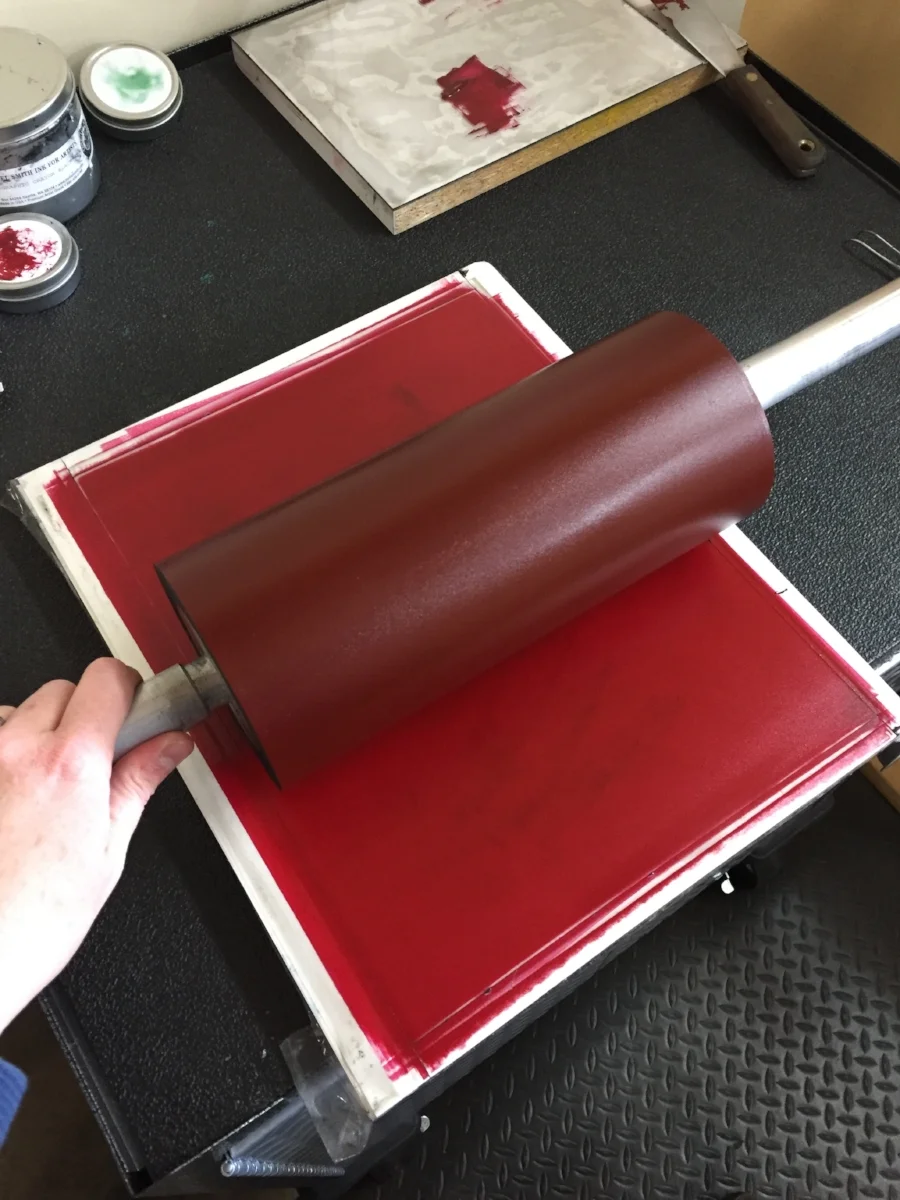

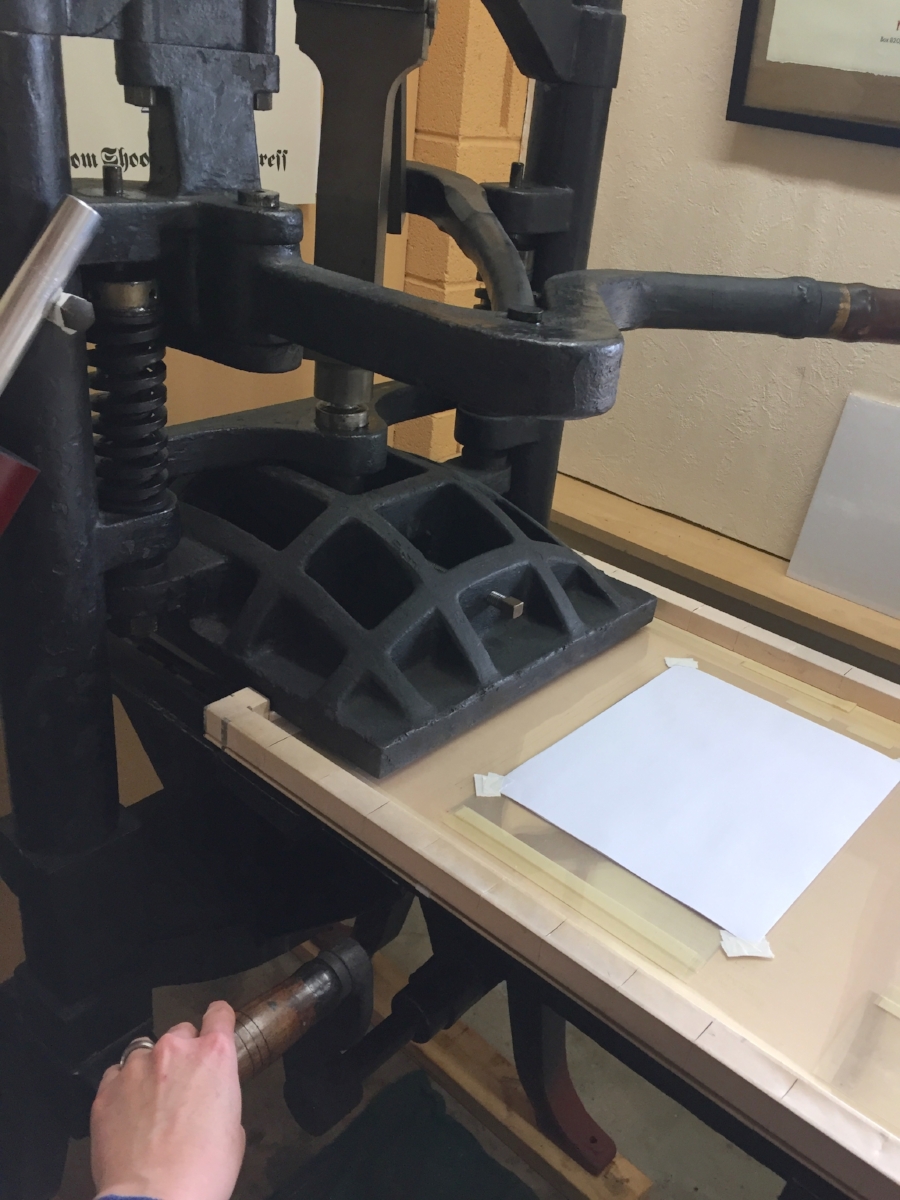

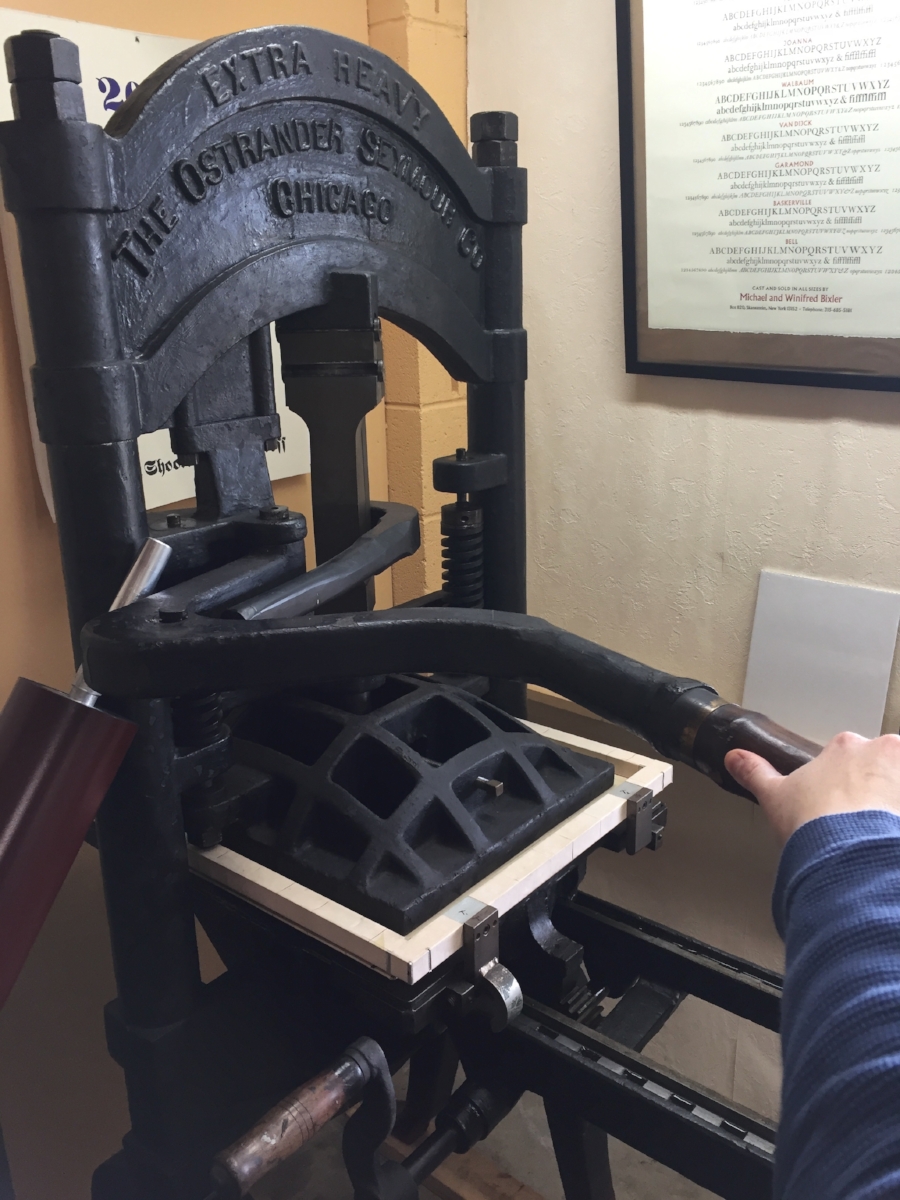

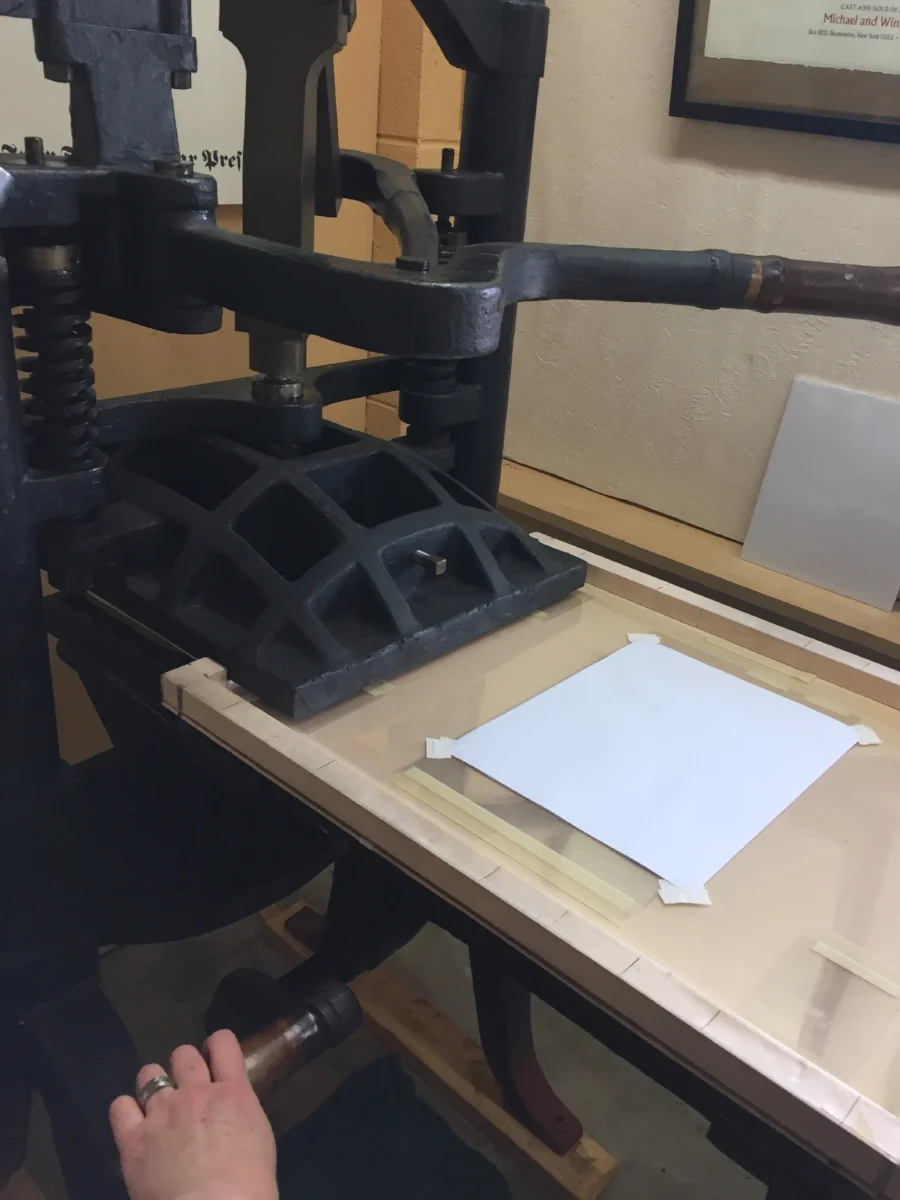

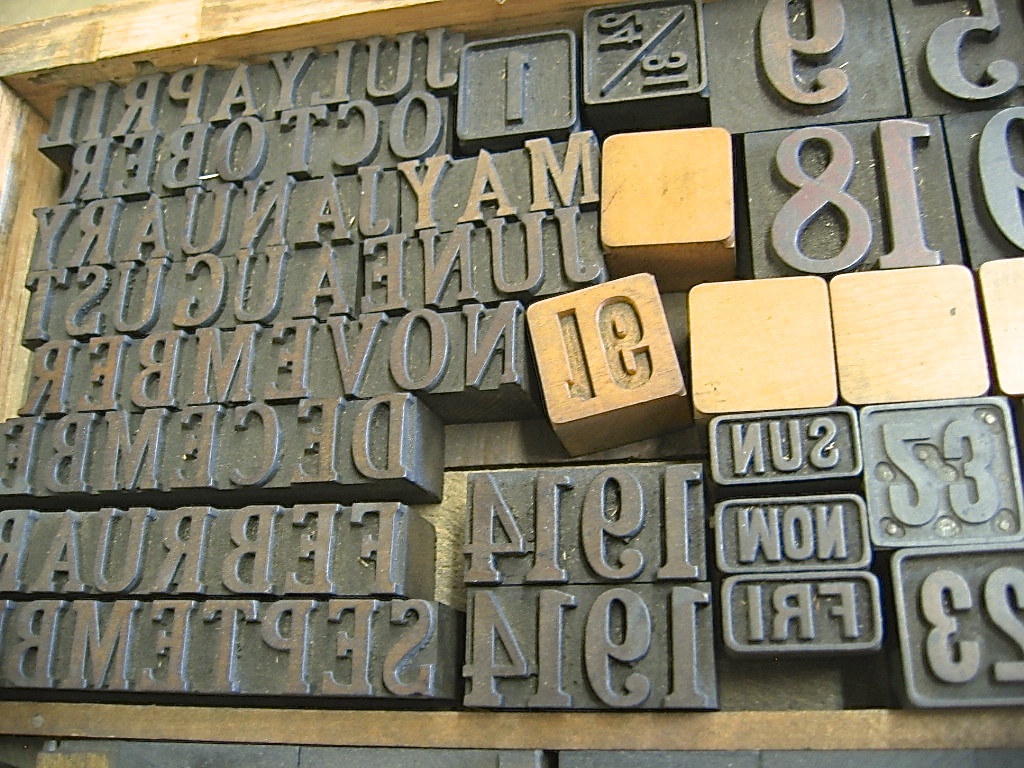

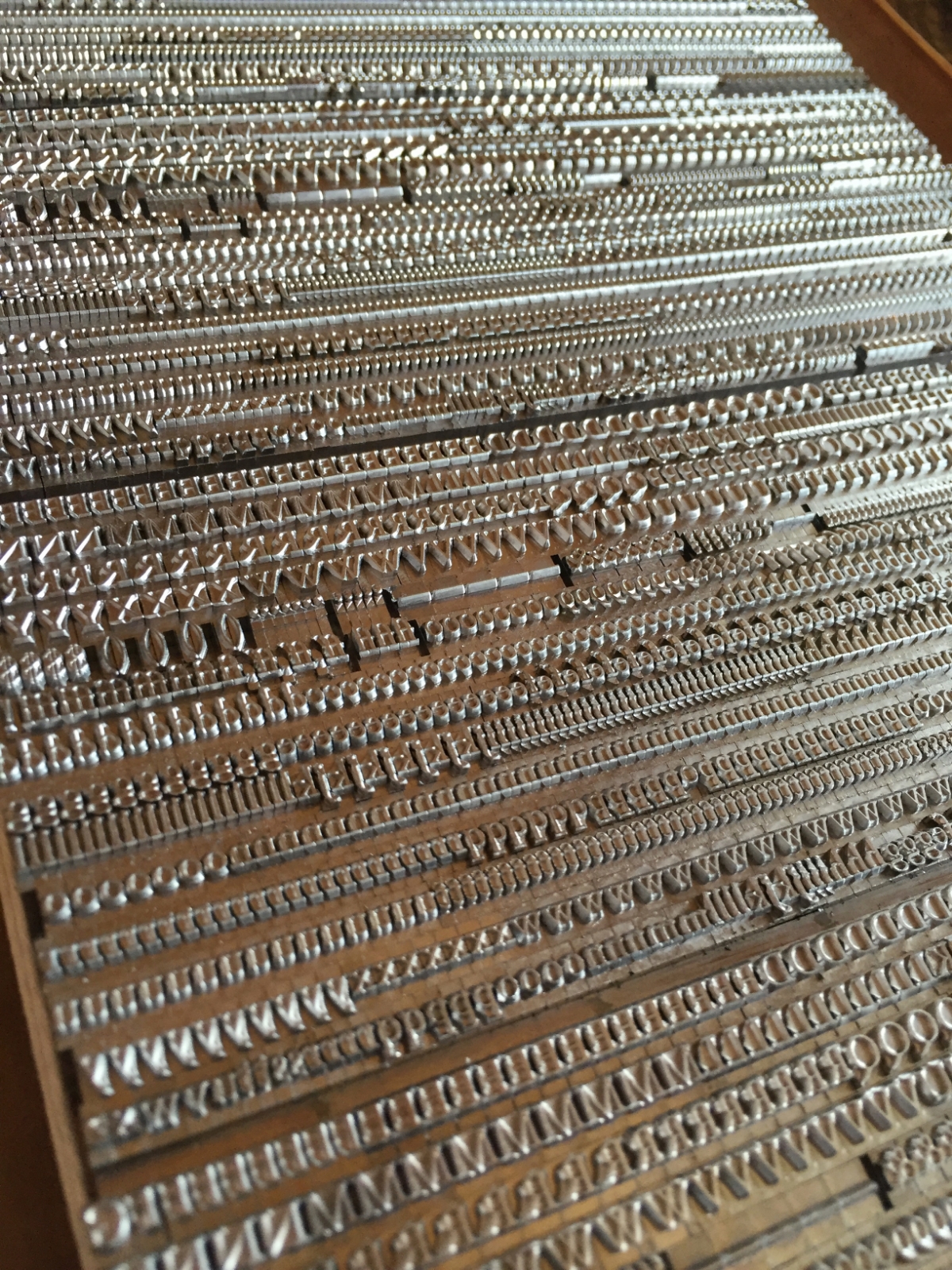

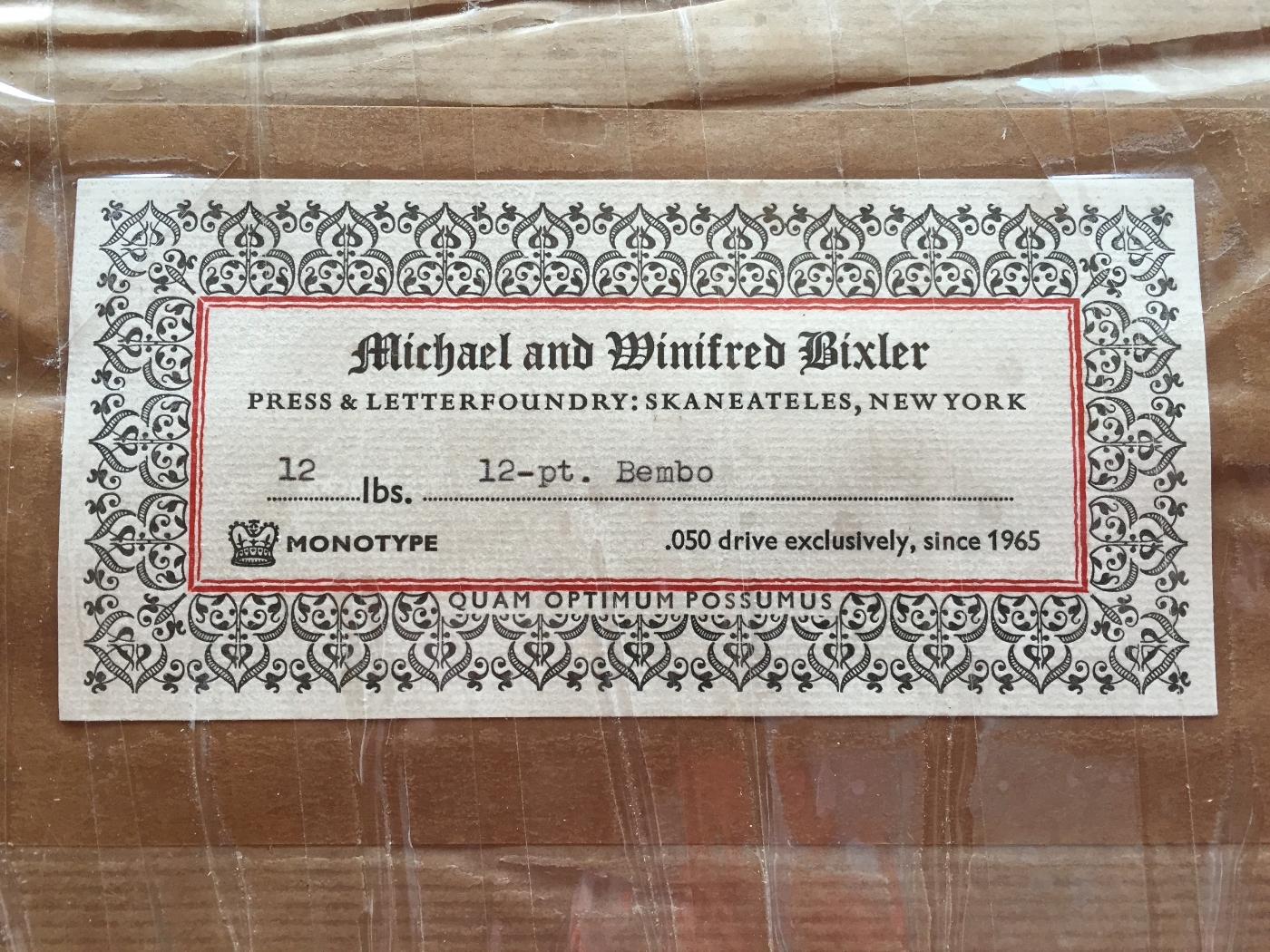

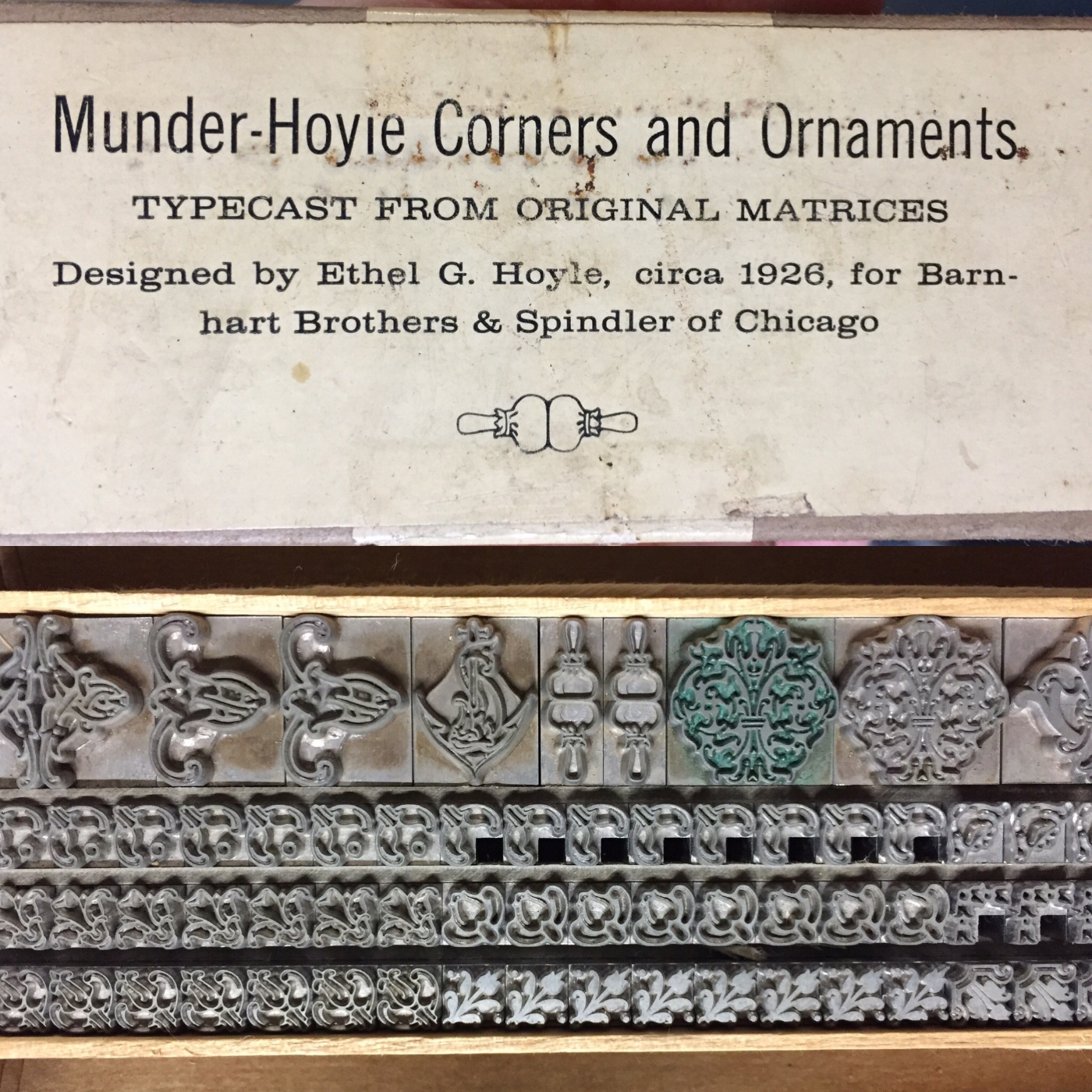

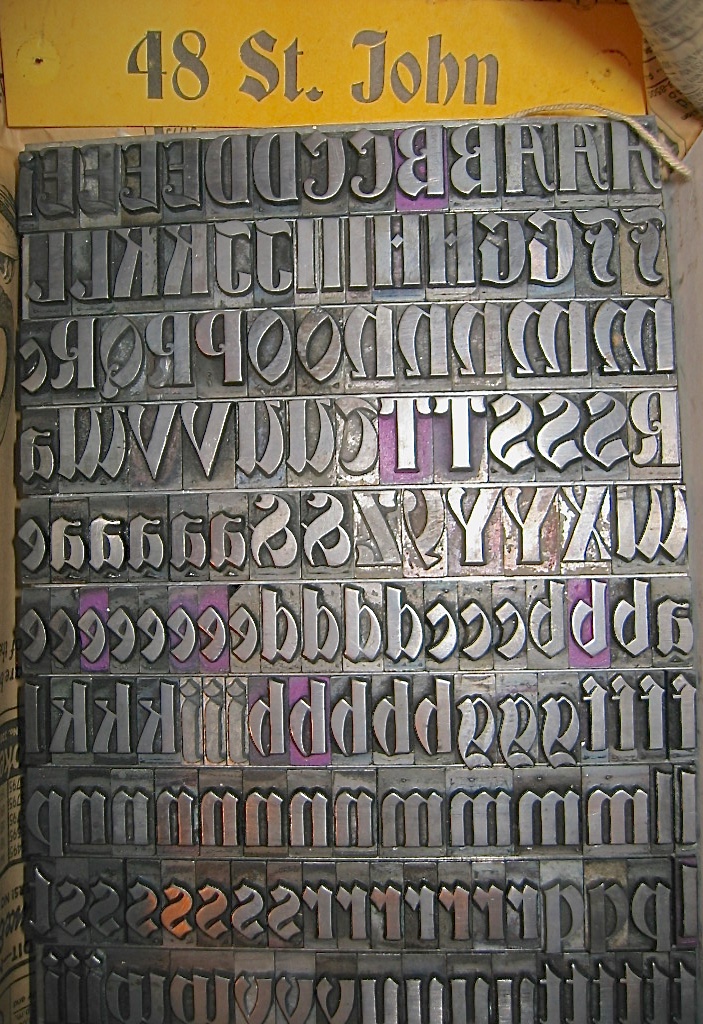

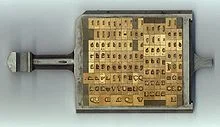

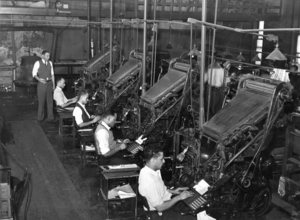

Next to the armory was a print shop. It had a ton of metal type, and a beautiful Golding press from 1916 and some Challenge presses. I went down there because we did a literary journal out of Risley, called the Risley Review, every couple of months, and we set that by hand. It was ridiculous; everybody that was on staff, like ten or fifteen people, would spend a weekend or so and just knock this thing out. It was really cool.

EH: And “setting by hand” meaning you actually went to the cases, [picked up] metal type letter-by-letter and space-by-space, and created the Risley Review.

JS: Yep, and it was beautiful and ugly at the same time. [laugher] From one page to the next it would be a different typeface. You couldn’t do the whole Risley Review, even at only 24 pages; we didn’t have enough type even for that. But we made do. So I got into [letterpress printing] that way.

When I was a junior I took a class at the Rare Books Library, in the library at Cornell, Olin Library, on the history of the book. The professor, who was the head of the Rare Books Department, used to show us amazing stuff — really beautiful books, old books. I saw some Blake there, the Arion Press edition of Moby Dick, stuff of historic value like Shakespeare and also great examples of modern day printing (like one of the original editions of Ted Hughes’ Crow, with Leonard Baskin’s illustrations). Don Eddy was the professor’s name. He was this big, portly guy, and he would put this stuff down on a table for you to see. We met in the library, like 7-9pm once a week, so you had the whole Rare Books Room to yourself, since it was closed. He would kind of stand over you like The Hulk and wave his arm and go, “LOOK at this! Just look!” Meaning, “Don’t touch. But LOOK at this.” One of the things you could do for final project was do some [letterpress] printing. So I did a small book of my own stuff called The Insane, which was about six poems and some linocut art by a young artist who was in Risley as well named Tom Williams, who did great stuff.

EH: How did that affect your own writing? Or did it?

JS: Well, it takes a long time to set a line! [laughter] I could say that it shortened my lines up, but it didn’t exactly do that. [laughter] But it gives you an appreciation for the craft of the book and the meaning of the book over time, and it’s just a lovely art, as you know. There’s nothing like seeing the three-dimensional quality of a word that’s set in type and printed in ink on a nice piece of paper, the bite of the type into the paper and stuff like that.

EH: Then you went from printing a la Gutenberg to digital publishing! How did that happen?

JS: Ten years of bookselling gives you a lot of time to think, about your life and things. [laughter]

EH: While you’re giving away copies of Tranströmer to anybody. [laughter]

JS: That’s right, while giving away copies of Tranströmer! I think it was 1999. I was not partying like it was 1999, but I was living in Charleston [SC], where people do still party like it’s 1999, and I had some friends that I knew in the local Tibetan society. My wife and I were good friends with the Tibetan Buddhist monk who was the teacher at the society. We had dinner with him a lot, hung out, took him places, and I met a couple of guys there who were doing web-based businesses.

At that point, Amazon was doing this [promotion] where you’d buy a book and they promised to ship the book to you and you’d get it in 48 hours or it would be free. Self-publishing was taking off and on-demand publishing was taking off, but for independent authors who were self-publishing there didn’t really exist a way to do on-demand printing. They’d say it was on-demand, but they really meant the distribution was on-demand to bookstores. You’d have to pay one of these on-demand vendors a lot of money up front, both to format your book and then to print and store 20 to 50 copies in a warehouse, and you pay warehousing fees. Your royalty was ok, it was better than an average author’s royalty, but it was still like 25%; and it was tricky, fine-print stuff, like 25% of the net, and the net was minus the cost of storing your book. So, it just seemed like a scam in a place where there was a revolution that could be taking place.

So, I went to these friends, three other guys. One had print shop experience, one had money, and one had internet marketing experience. I was like, “Let’s print and ship a book in 48 hours or it’s free.” Let’s create a way that we can format any author’s book. It doesn’t make a difference what their aspirations are — it could be that you found your grandfather’s WWII diary in your closet and you just wanted to preserve it by having it printed out as a book. Or it could be that you wanted to sell your science fiction novel and make a million dollars. It could be for any reason, right? But that you could have a book that doesn’t even exist, and it could be printed and shipped in 48 hours.

So that’s what we started off with, with a company called GreatUnpublished[dot]com. We hit the ground running, we grew quickly, I made the rounds talking at the Virginia Festival of the Book, Text One Zero in New York, and we went to the major book fairs, the [American Booksellers Association] fair, and spoke at the Arizona Book Festival, etc. We went out and met authors who were signing up with us, and we went from 6 or 7 authors in our first month to over 10,000 between [the years] 2000 and 2003. It was really cool.

Eventually the business part of it got away from me, where I wasn’t as much interested in it anymore. I had that, “My job here is done,” kind of feeling, and I also had my first child. Nothing against Charleston, South Carolina, but I did not want to raise a daughter [there]. It was a very black-and-white city, black-and-white world, still a lot of sexist cultural residue there. I was feeling like I needed to get out, so that’s how we ended up coming to Virginia. That company, which went from being just an author-initiated publishing company, to a vendor that printed and distributed books for small presses, and then for medium presses, that company became BookSurge, which then sold to Amazon in 2005. It is the print arm, to this day, of CreateSpace. If you self-publish a book using CreateSpace, it comes from this company that we started in the back of this print shop in 2000 in Charleston, S.C.

EH: You have been quite the time traveler — you’ve printed like it’s 1500 and you've printed like it’s 2150! [laughter]

JS: That’s right! I’ve always loved books in any form. I’m not a purist, clearly, or I wouldn’t have jumped into on-demand stuff. But that doesn’t mean I don’t appreciate the really beautiful art and craft of the book. It’s since been blown into a million pieces by technology, but at that point [in the early 2000s] the publishing industry was a really tight place to get in. If you wanted to self-publish there was this huge stigma around it, and that kind of ticked me off because, as a writer you really have to self-actualize. You have to figure out what is best for you to write, what is best for you to do. You can’t just be writing to the market. Some people do write to the market, especially mystery writers, genre writers, writers of contemporary novels, and if that’s what they like to do that’s awesome. Because then they are truly self-actualizing themselves, right? They’re doing what they want to do. But not everybody wants to do that. When I first started and we were dealing with the friction of, “Oh, this is vanity publishing,” I was like, “So this means William Blake was vanity…”

EH: And Walt Whitman.

JS: And Walt Whitman, and ee cummings, and…

EH: And Anaïs Nin. There was a recent article on Brain Pickings that showed her publishing her book, and she’s treadling her old printing press!

JS: Yep. Somebody’s going to publish it, and it doesn’t have to be somebody else, right? I remember being at the Virginia Book Festival, and I was on a panel with some other self-publishers and people from the larger publishing industry. We were fielding questions and somebody was saying, “Aren’t you afraid you’re going to flood the world with bad books?” And I just kind of spread my arms and said, “Go down the street to Barnes and Noble and look around you. The world is already flooded with bad books!” [laughter] There’re tons of bad books out there! You can add yours to the mix. But it’s not about good books and bad books. It’s about making something public. That’s what publishing is. And it’s ok if the market is 20 people; it’s ok if the market is 20 million people. It doesn’t much matter.

EH: So what are you working on lately?

JS: Ok, so I’m working really closely with an amazing letterpress printer at St Brigid Press to put out a chapbook in the Fall, right?!

EH: Yes, indeed! It’s called Wind Intervals, folks. Stay tuned.

JS: And I’m really excited about it, because outside of some magazine publicationsI’ve always chosen the self-publishing route. I’ve never been bothered by that. So, outside of Beloit Poetry Journal, the New Orleans Review, and a few other really small presses that have done individual poems, this is the first book I haven't had control of.

EH: [gasp, laughter] Wow! Although we’re working closely together about design and all of that.

JS: It’s in very good hands, very good hands.

EH: And this will be a collection of six of your poems, plus a couple of nature prints that we’ll do here at the Press. Hopefully forthcoming by August or September. In the meantime, you’re continuing to write. Would you like to read us some of your poems?

JS: I would love to. In our monthly group, there’s kind of a competition between some of us, or an imagined competition, of who can come and read the poem that they just finished moments ago. So, in the spirit of that, I wrote this last night. I’m reading you something that’s so fresh that I don’t even know what it will sound like when I read it.

EH: All right! We are ready.

JS: It’s called “Stillness in a Low Time During the Rainiest Month of May in Half a Century.” And it’s felt like that, right? There’s been so much rain here in Virginia. I think it’s the 20th today, and 19 out of 20 days we’ve had rain, and I’m not exactly used to that.

Stillness in a Low Time During the Rainiest Month of May in Half a Century

The cars approach and diminish but the road goes nowhere.

The storm stands across the street and says go.

Panic fans out.

The grass migrating without moving.

One blade bending to talk and the other

to listen … but to some other voice,

arriving from a distance. A voice with the tongue of a shadow

as if all this light traveling ninety million miles amounted

to a message smaller than a grassblade.

How small this poem must be in the field of minds!

I heard some people talking as they walked

across the wide green library yard, laughing

at a study suggesting that plants and trees

communicate. One bent his head toward the other,

whose face, angled away from the sun,

was obscured in the late afternoon shadows.

EH: That is beautiful, Jeff.

JS: Thanks! Keep saying stuff like that. [smile] You know we had a huge fire in the national park here [Shenandoah National Park], that lasted a couple weeks, [burning] 8- or 9000 acres. It was the biggest fire in the Park’s history, and it hit a part of the Park that had not seen fire in 80 years. So it was just ready to burn. They think it was caused by human carelessness, but that part of the Park needed to have the underbrush and the leaves and stuff burned out, so it’s actually a good thing for the Park. One of the cool things that happens after a fire like this that’s beneficial when that undergrowth burns away, is that it gives space for trees, it gives space for saplings, other plants come up. You have these flowers that are referred to as “fire followers.”

I first read about this and wrote this poem a couple years ago, when there was a fire a couple years before on Mt Diablo in California. There were scores of botanists and scientists and biologists who were scrambling to be there in the spring, because there were going to be flowers that nobody had seen in their lifetime. They only come out after a fire, because it takes intense heat to crack the pods so that these things can grow. And then they’re only around for a couple years and then they disappear again. So all these scientists who knew of this type of flower but had never seen it, it was a really exciting time for people. It made me think a lot about stuff, and so I wrote this poem called “Fire Followers.”

Fire Followers

In the spring after devastating fire

they grow only here on the back of the devil

whispering bells and red maids, golden eardrops

blazing star with its spiky leaves and yellow flowers

and in the scorched canyons harder to hike and even then

for just a few weeks the fire poppy flicks gold notes

Under the pressure of smoke and firestorm and ash

the seeds break open then in the spring surface and bloom

For the only time in a generation or longer

the inclines of Mt Diablo are covered in gold red and purple

Gone in a few years and back to something buried

by what we see as the normal brush and vine and trees

Who knows what seed dormant inside us may burst

into quiet small beauty brought to birth by the worst

that can happen who knows how long it will last

this beauty not normally us and not someone else

EH: That’s tremendous. And again, the interior and the exterior landscapes.

JS: Yes. And if there’s anything I want anybody listening to take away, it’s “Go read Tomas Tranströmer, and go read Mei Yao-ch’en and Tu Fu and Li Po and these great Chinese poets of the T’ang and Song Dynasties.” The poetry is full of this richness, where you can kind of telescope between your most personal, innermost feelings and thoughts, and the world that’s outside you. It’s really amazing stuff.

EH: Read us another poem or two.

JS: Ok, I’m going to try and grab something from Wind Intervals… This is called The Stones.

The Stones

Winter begins in the stones. In a dream the sky house

gets closer as if it is trying to hear a secret or tell me one

but when I can read its lips I see it is just pretending.

In the car: stones from a trip to the beach.

A thousand miles from where we found them

for months they have rested in a drink holder

with no discernible nature acting on them,

no car tides or car gulls have hampered their stillness.

Now when we pick them up on a drive we marvel

at how cold they are on this mild first day of November.

You can press them to your hand, your neck, your cheek

and they stay cold. They are telling me a secret

without moving their lips or pretending to tell me anything.

They are coming closer without moving, like snow clouds.

EH: That’s one of my favorite of your poems.

JS: Thank you.

EH: Can we have one more?

JS: Yes. I’ll do “Wind Intervals,” [the title poem] from the forthcoming book.

Wind Intervals

In a space under trees I can hear the wind that is not here

like a can kicked across the street by a boy still coming

or as if the act of the boy shaping his mouth to shout

made a sound before the sound of the shout

What is the word that I hear before the trees

above me shake and give the wind a momentary word

What is the sound of a loosening of leaves

like forgetting hands just before they drop

to our sides? The interval of apprehension.

The time we are alive. The boy stepping up the curb.

EH: It is such a pleasure to hear the poems from the mouth of the poet. Thank you so much. This has been fantastic to have you in the pressroom speaking about all of these precious things and reading your work. Thank you!

JS: Thanks. Always great to talk to you.

EH: For more information about Jeff’s poetry and prose, you can visit his website, “Translations from the English,” at jeffschwaner.com. And to learn more about St Brigid Press and the work we do here — and to follow along with the forthcoming Wind Intervals book — please visit us online at stbrigidpress.net.

Thank you all, and all best from the Press!

© St Brigid Press, 2016. All rights reserved.

No portion of the audio or transcripted interviews, images, or excerpts may be used in any form without written permission from St Brigid Press.

For more information, please contact us at stbrigidpress@gmail.com