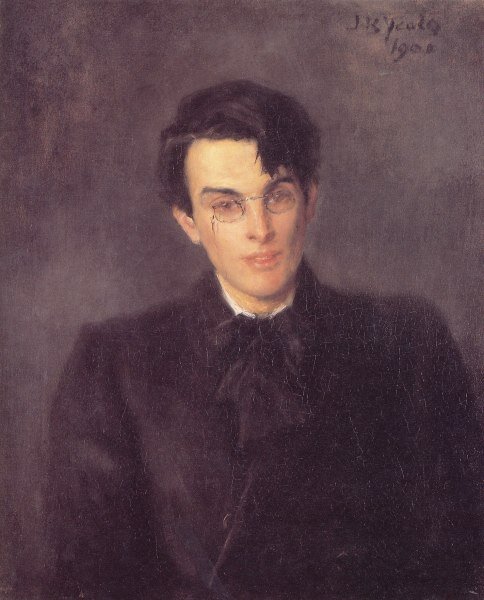

In his book Smoke Proofs: Essays on Literary Publishing, Printing & Typography, Andrew Steeves talks about an “ecology of literature” — the writers, editors, printers, publishers, bookshops, readers, and more who connect and support each other in the complex web of print culture. There is a similar “ecology of craft,” a system of relationships that fosters—that makes possible—any made thing.

Even before this era of social distancing, I spent most days alone in my basement print shop, making books. With the heightened awareness brought by increased long-distance correspondence, and by having just completed a new chapbook of poems, I’ve been thinking even more than usual about all of the people whose work makes my work possible. This post spotlights some of them, from the type founders to the thread-makers, who are indispensable to bookmaking at St Brigid Press.

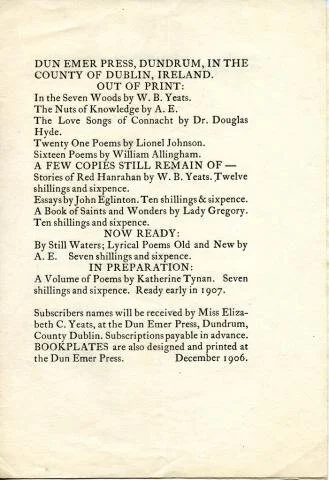

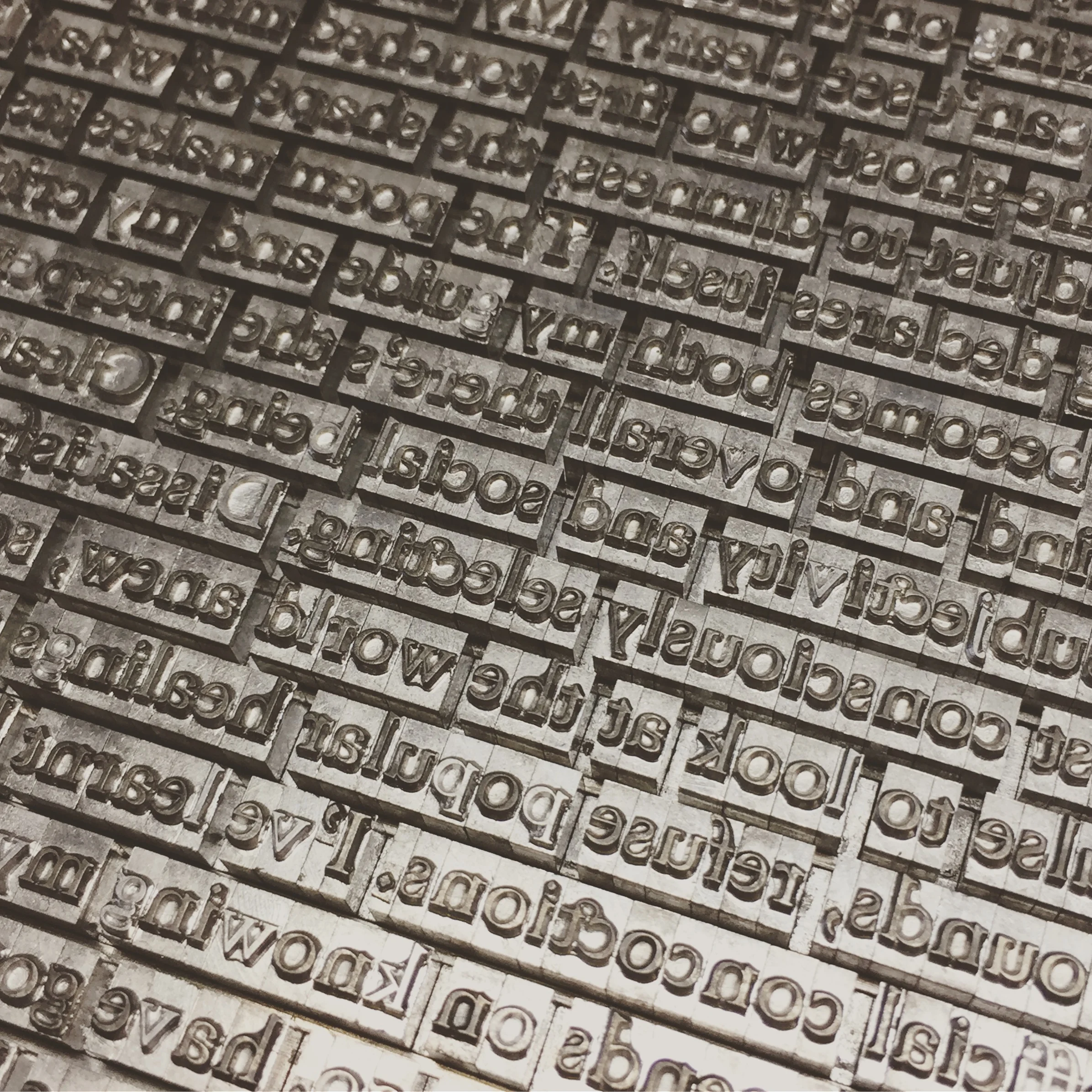

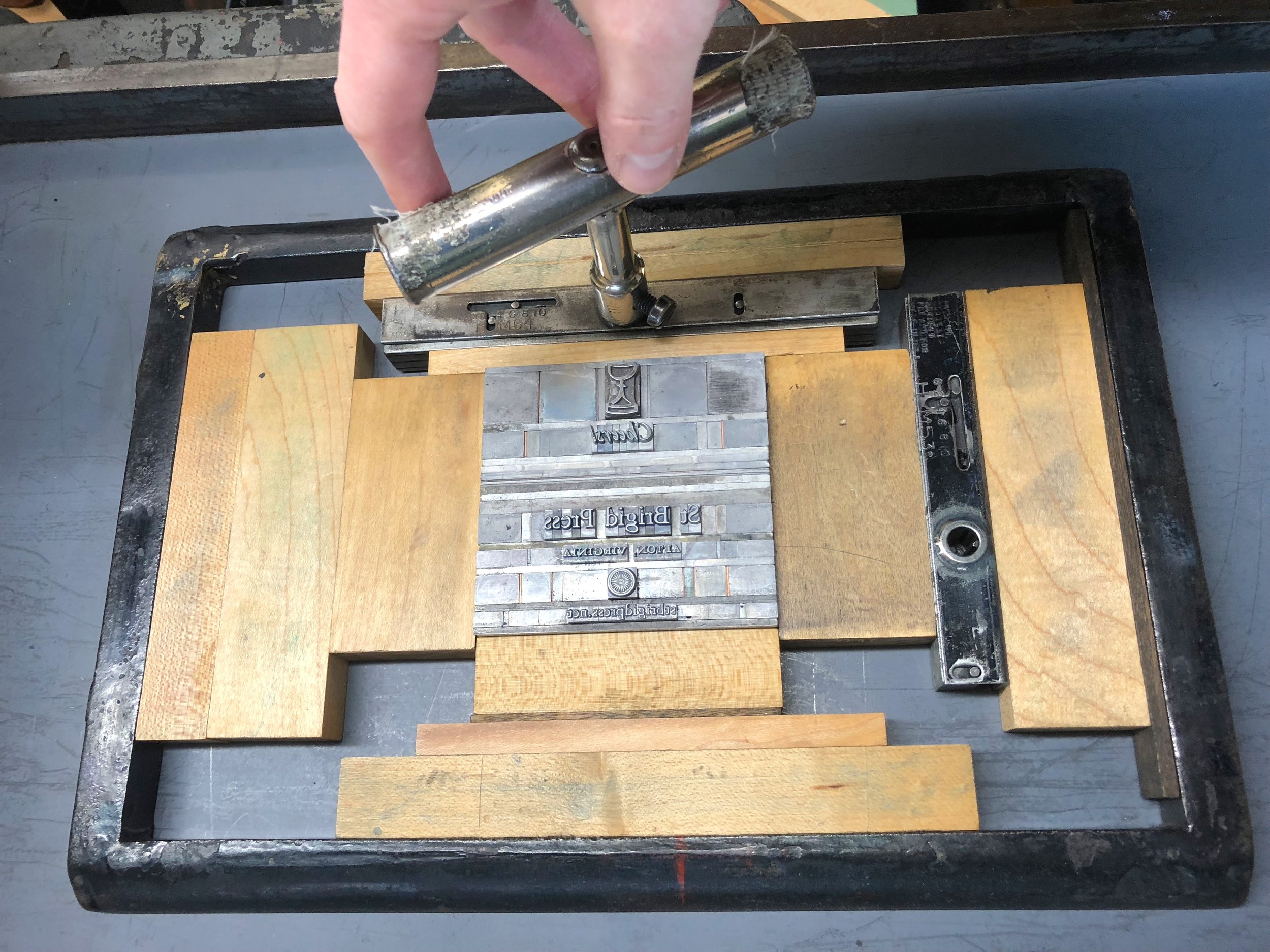

JUST OUR TYPE

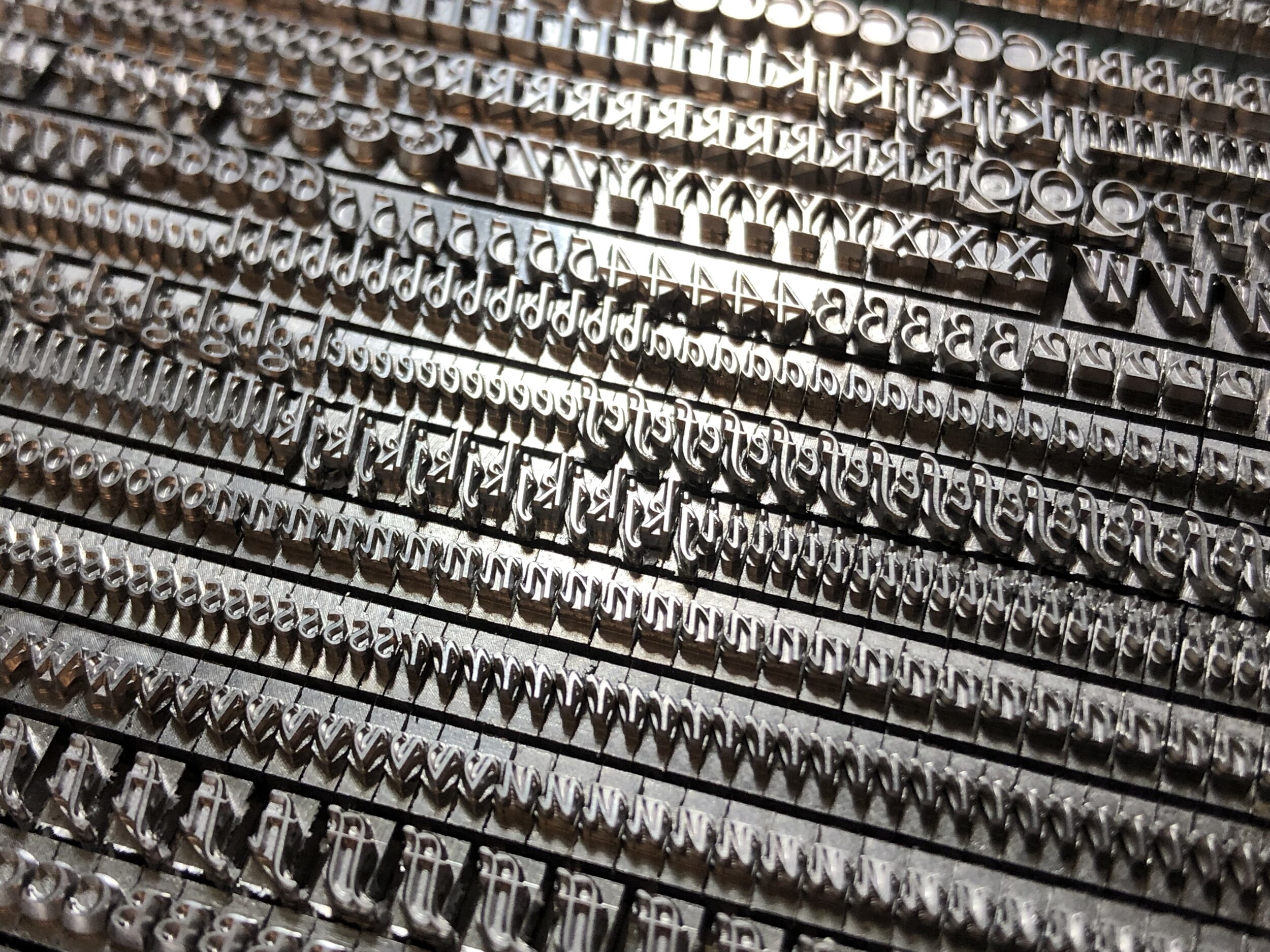

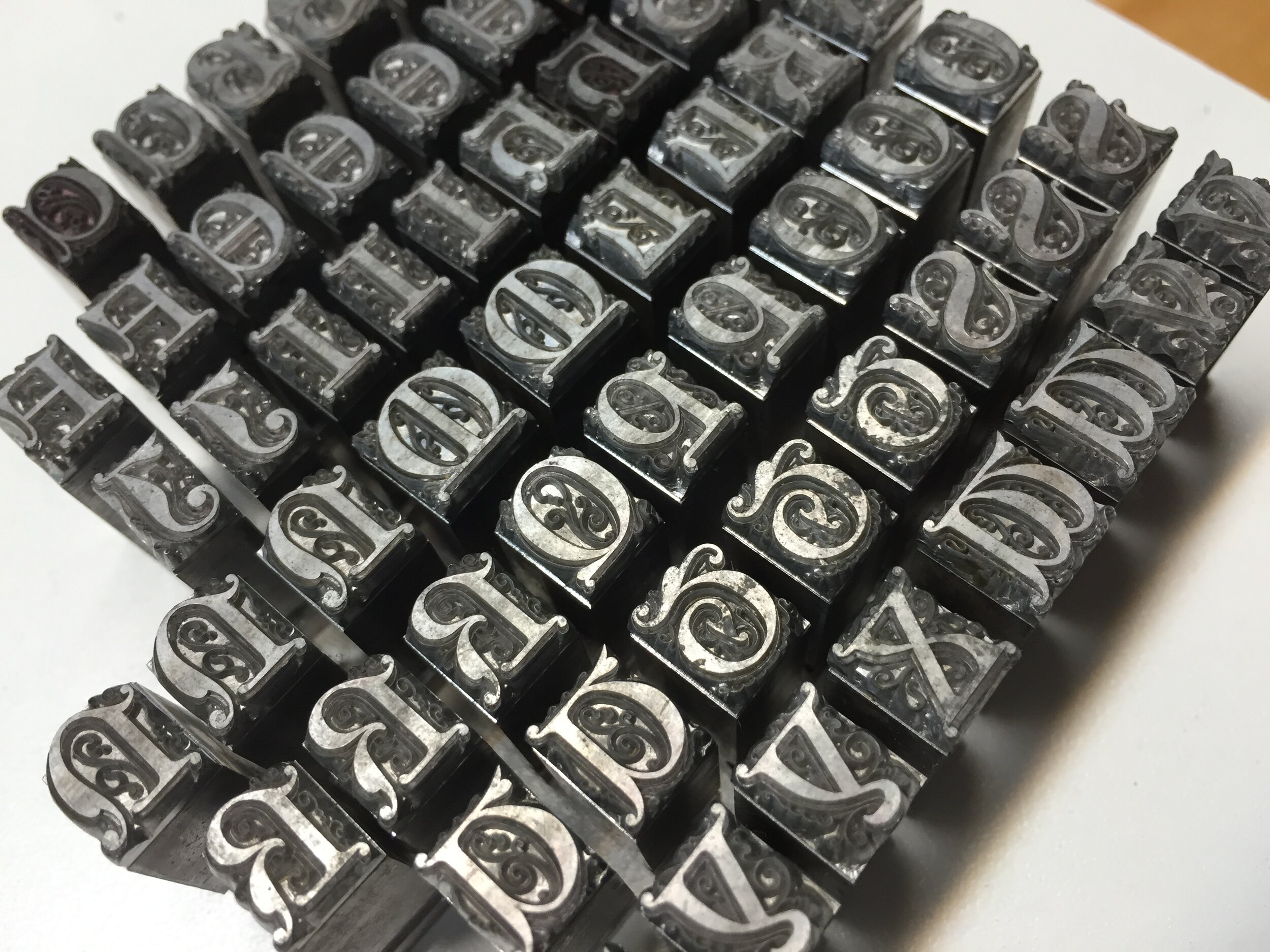

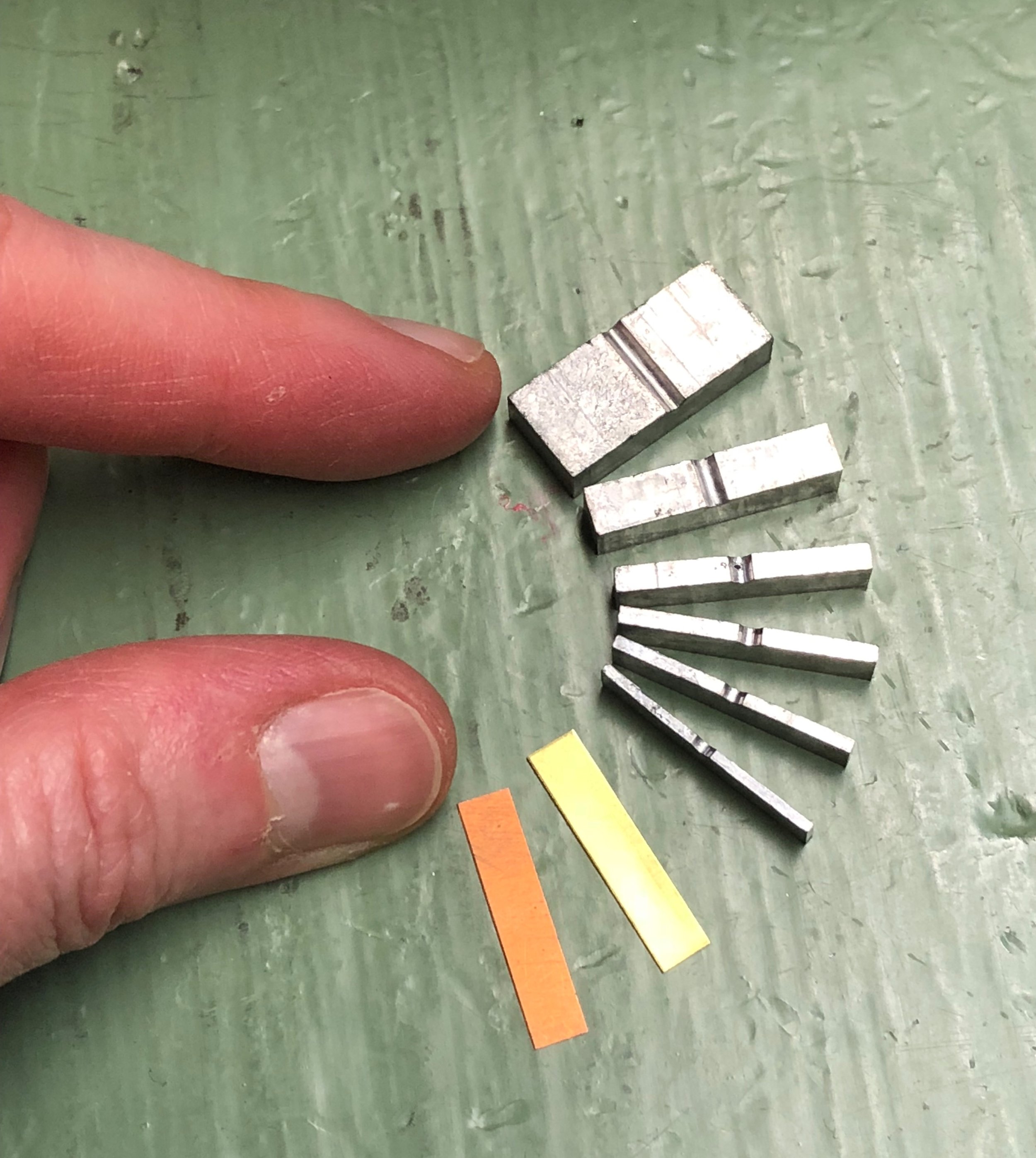

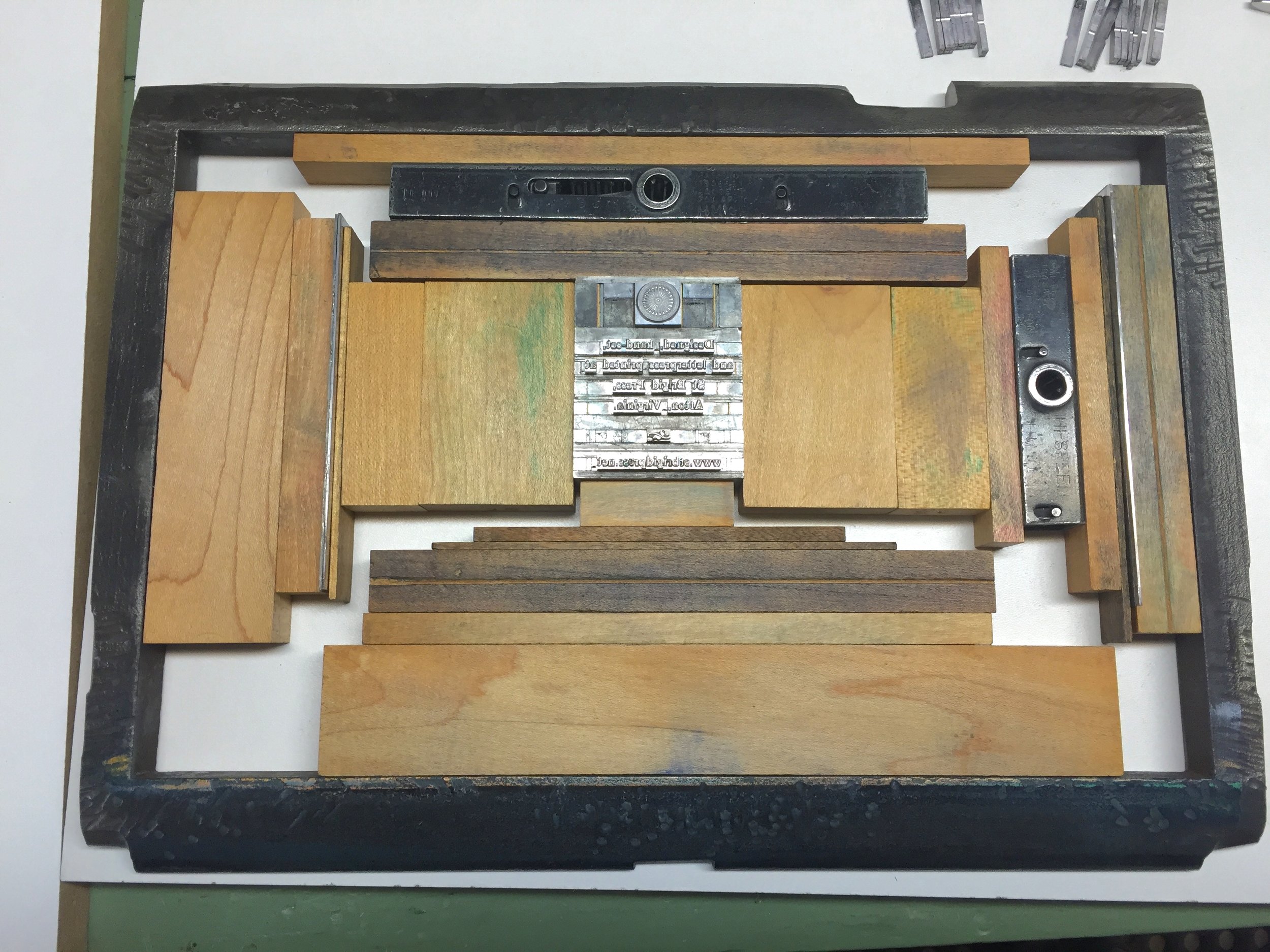

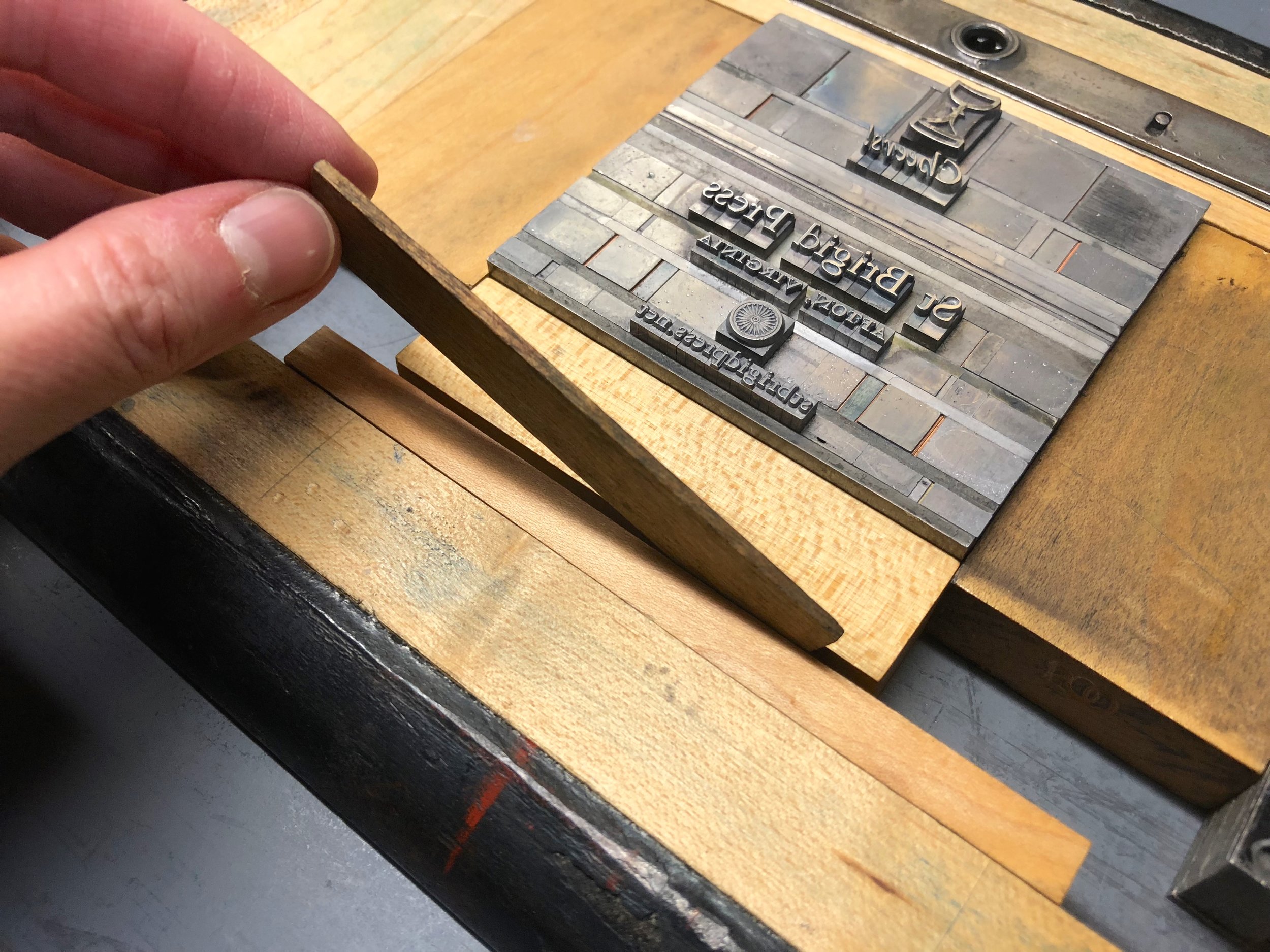

One of our most essential and cherished connections is with the people who make the metal type we use to print with. Type metal, a carefully balanced alloy of lead, tin, and antimony, needs to be precisely cast if it’s to print precise letters. Thankfully, there are a number of foundries in operation today, in the US and around the world. Much of our type comes from a few trusted sources: Michael & Winifred Bixler in Skaneateles, NY, Patrick Reagh in Sebastopol, CA, and Rainer Gerstenberg in Germany. These folks are all fine printers as well as have a deep knowledge and dedication to the historic craft of typecasting. Some of the superior types they’ve cast fill the cases here at St Brigid Press: Centaur & Arrighi, Bembo, Goudy Old Style, Koch Antiqua. In addition, we have a good deal of older type from various sources, precious hand-me-downs we’re honored to keep in use.

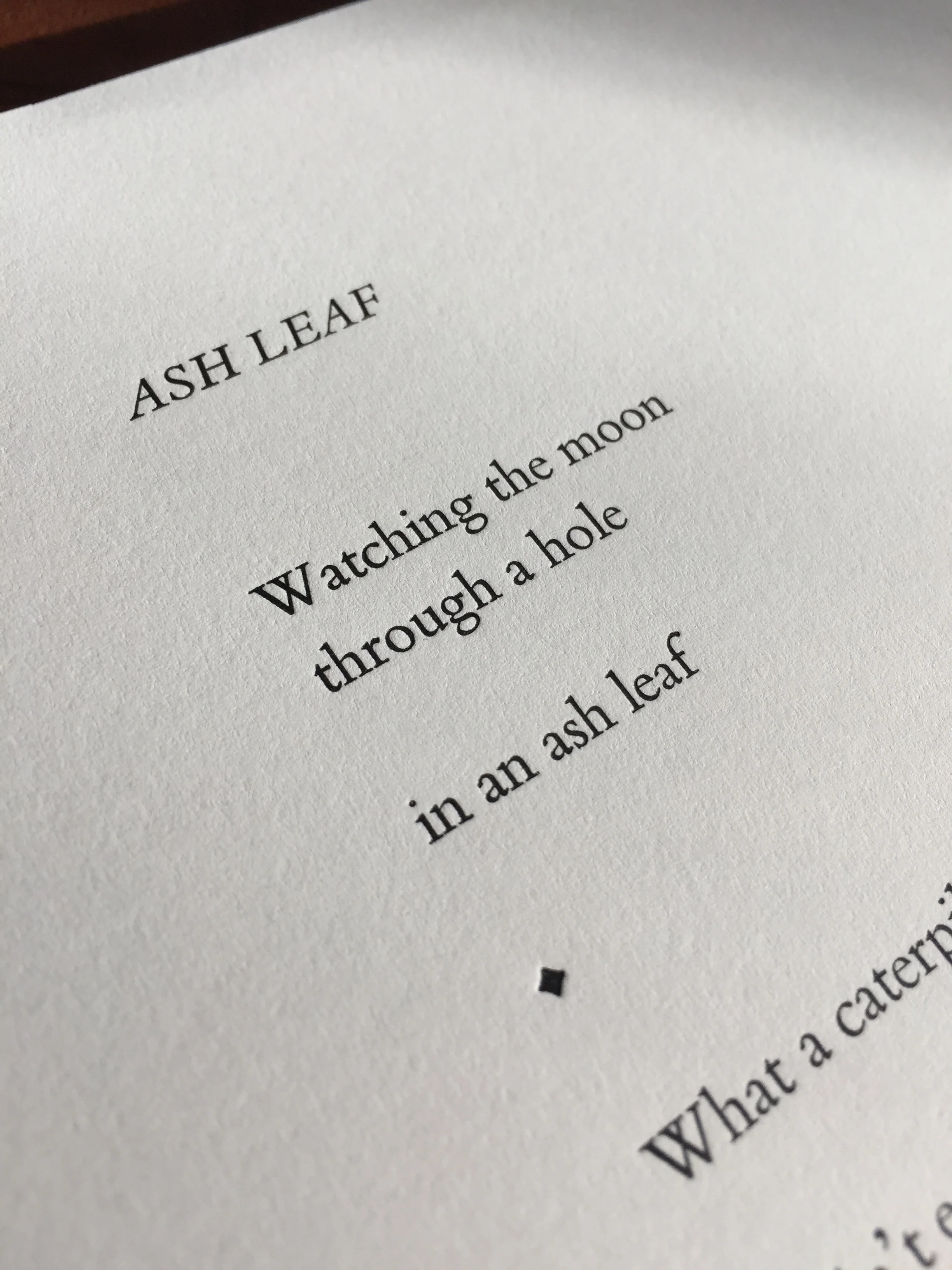

WHOLE WORLDS OF PAPER

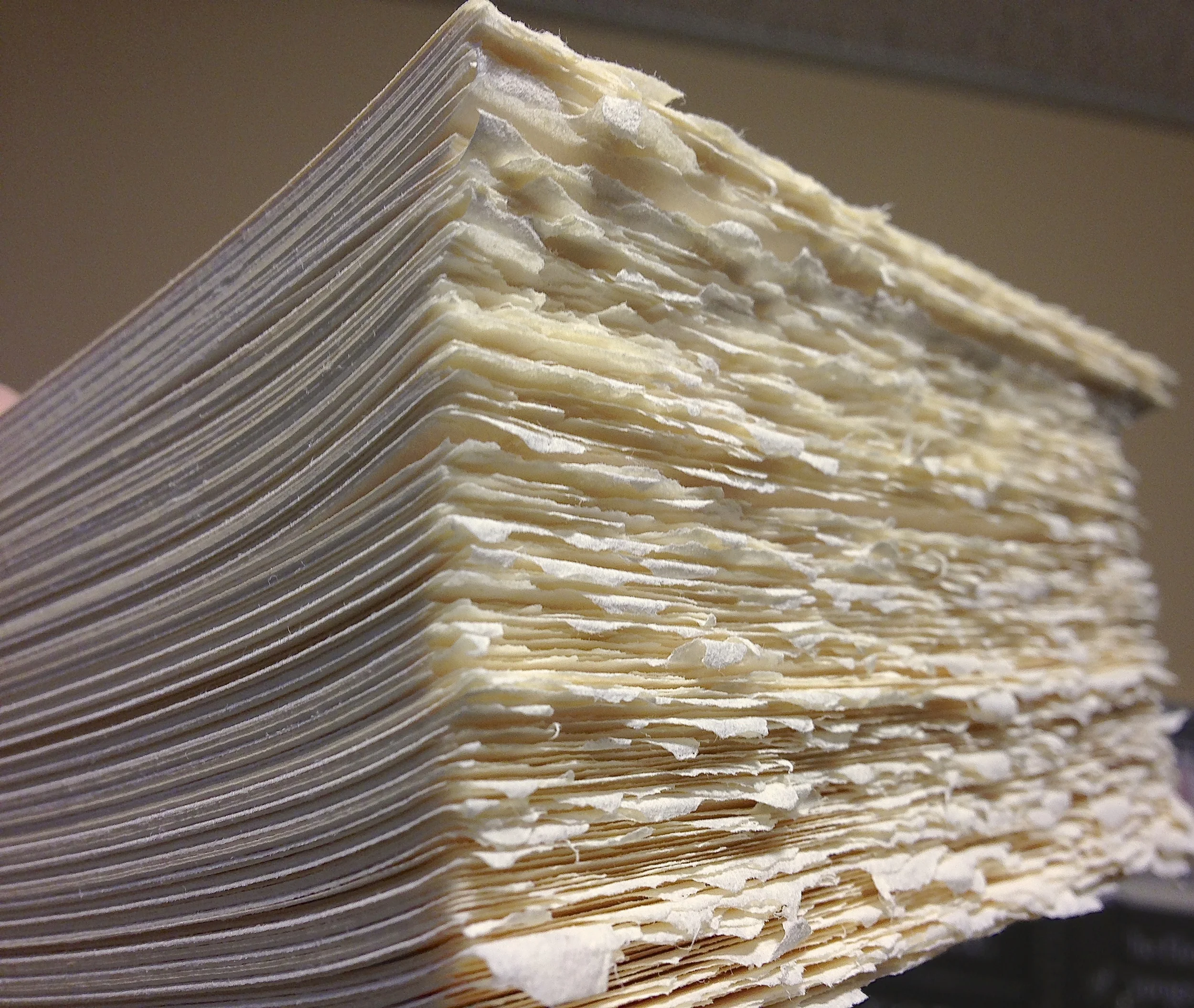

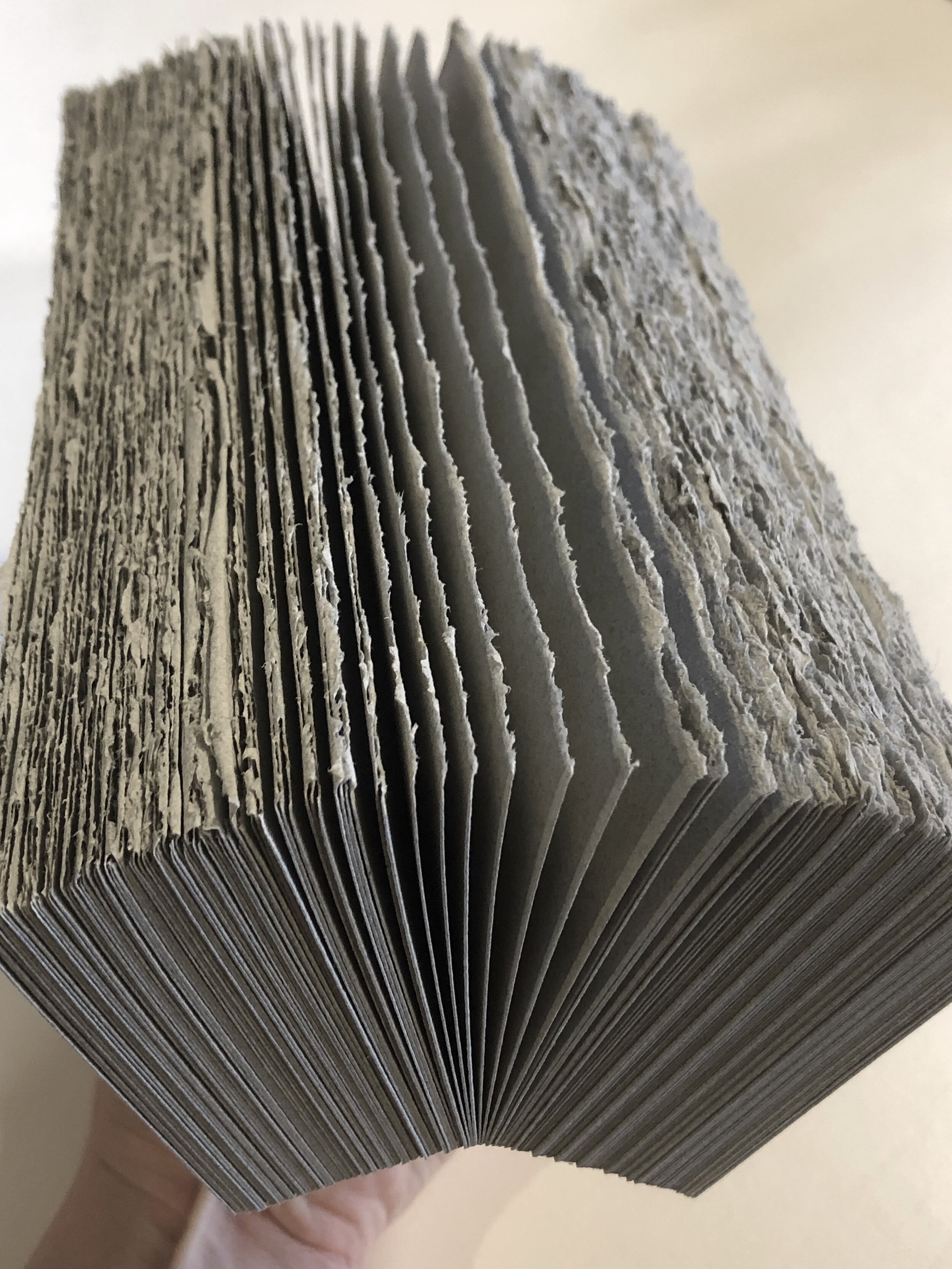

Sourcing beautiful papers with which to print beautiful words is a particular pleasure. And David Carruthers and his team at Saint Armand in Montréal have been supplying luscious sheets since 1979. We often use their thick handmade stock or machine-made stock for book jackets.

For text paper, we use Mohawk Superfine, French Rives, handmade Okawara, or others that are well-suited to the letterpress process. Our go-to paper sellers at Dolphin Papers in Franklin, Indiana, supply us with these, as well as with a kaleidoscope of Nepalese Lokta and Thai marbled sheets for decorative use. WARNING: Perusing pages and pages of fabulous paper is a serious rabbit-hole, and you may never emerge!

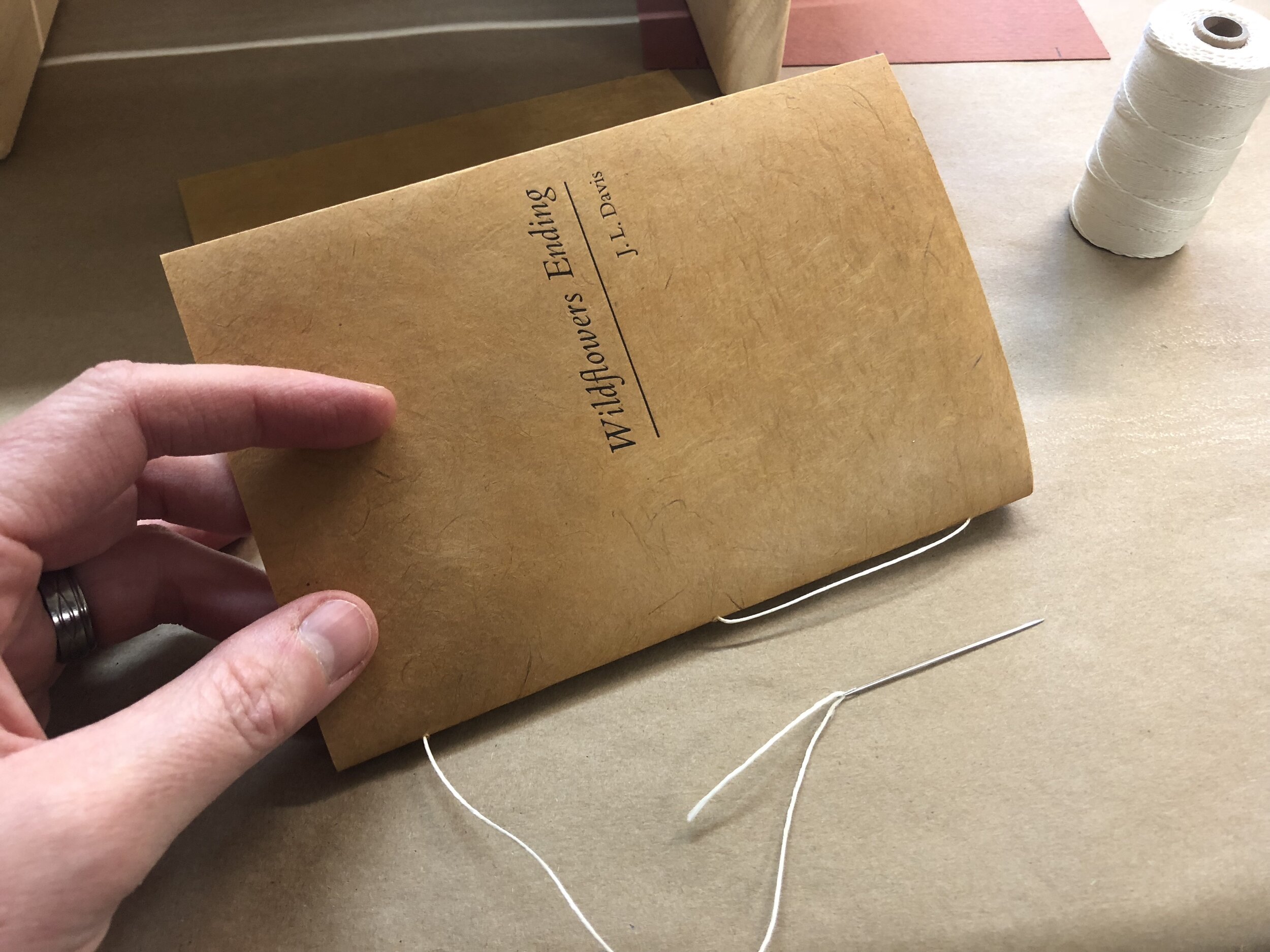

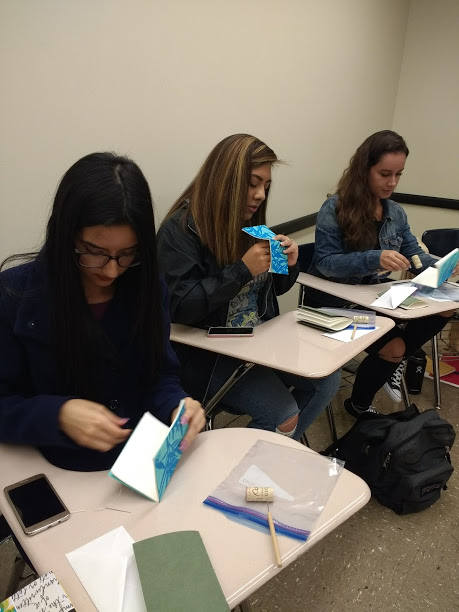

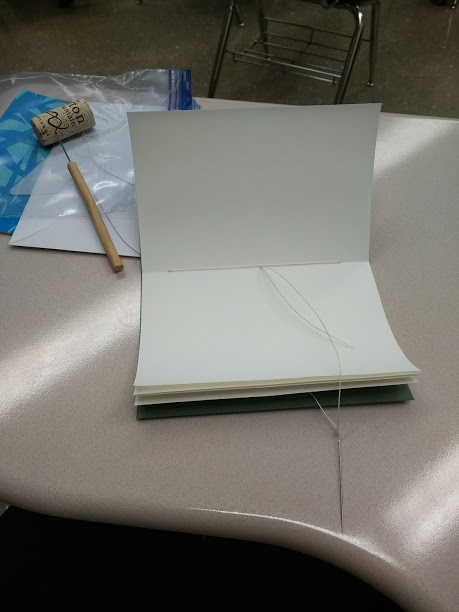

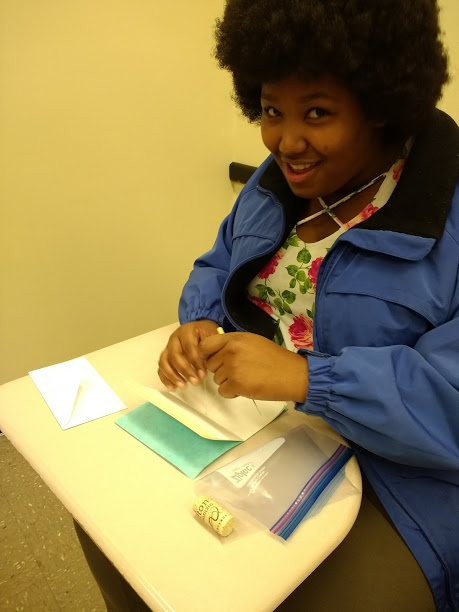

SEW IT UP

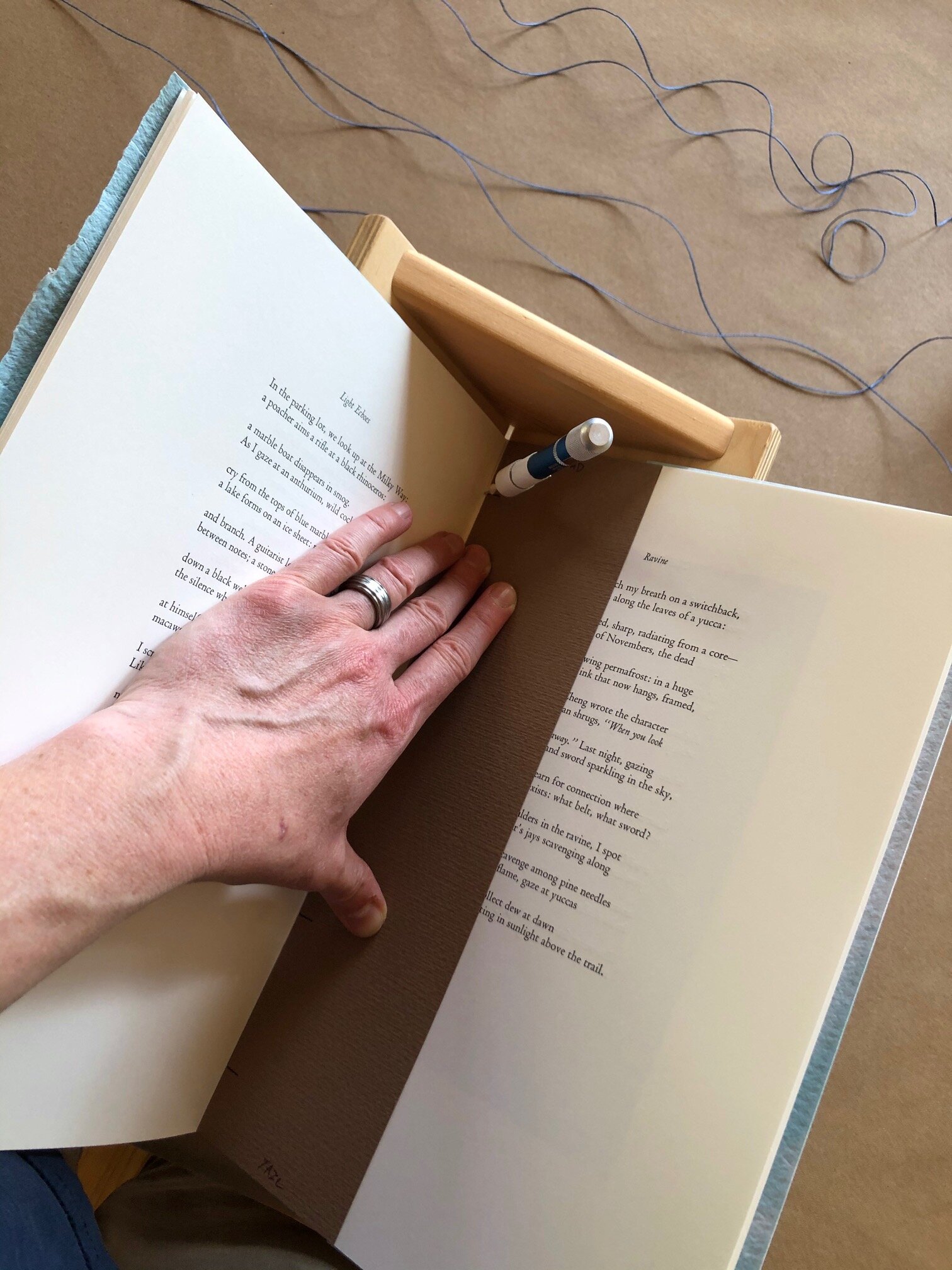

One of my early discoveries on this adventure was how much I enjoy hand-sewing. My mother, grandmother, and great-grandmother all sewed (garments and quilts), but I did not have much experience in this craft until learning the rudiments of making a book. I began experimenting with various needles, threads, and awls, working out which tools worked best for my purposes. For most books, I use Richard Hemming & Sons Darner #3 needles with unwaxed Irish linen thread in either 12 or 18 weight, both from Talas in NY. For years I’ve used a well-made cradle from Jim Poelstra in California to hold the book blocks while punching sewing holes.

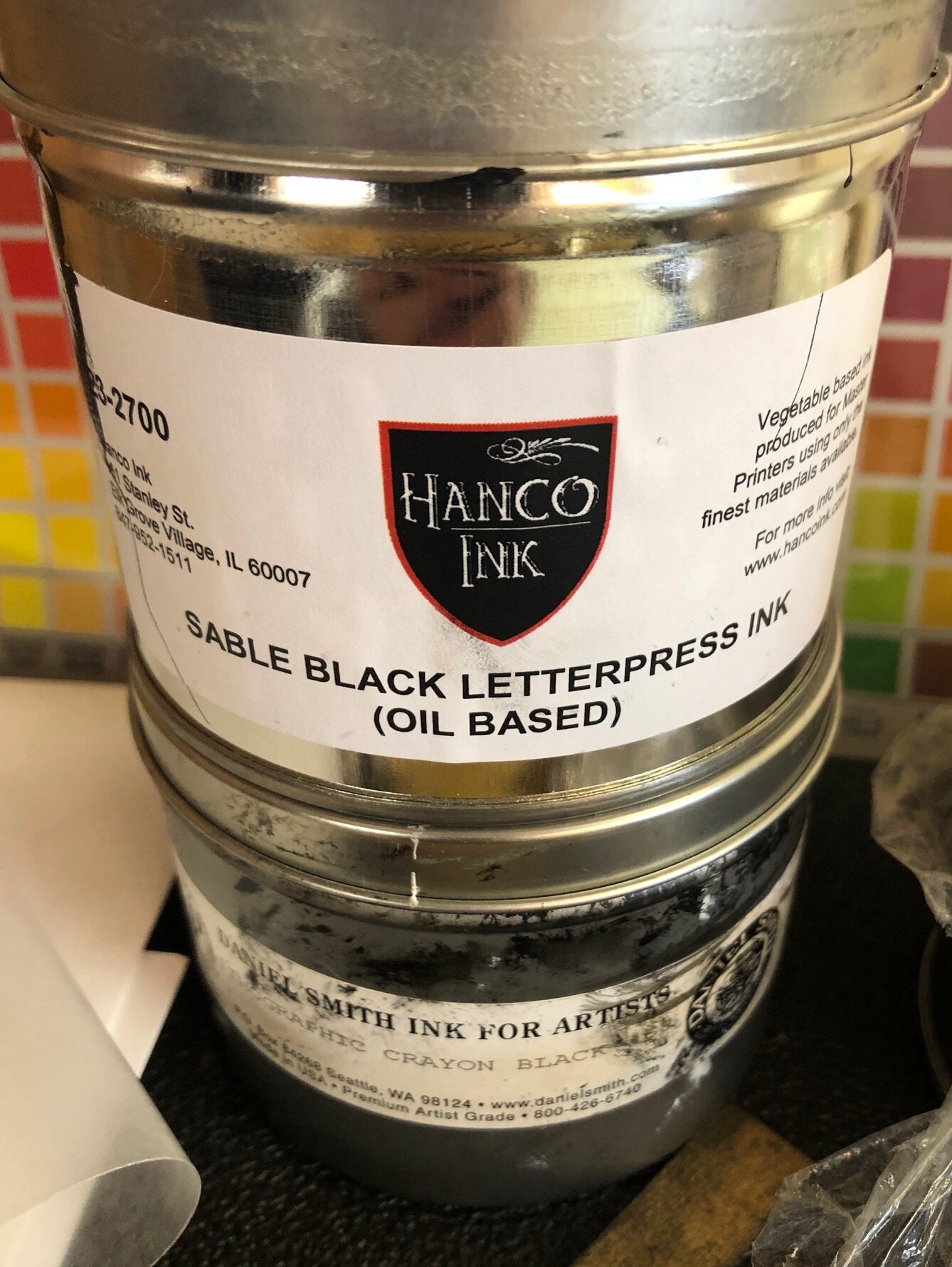

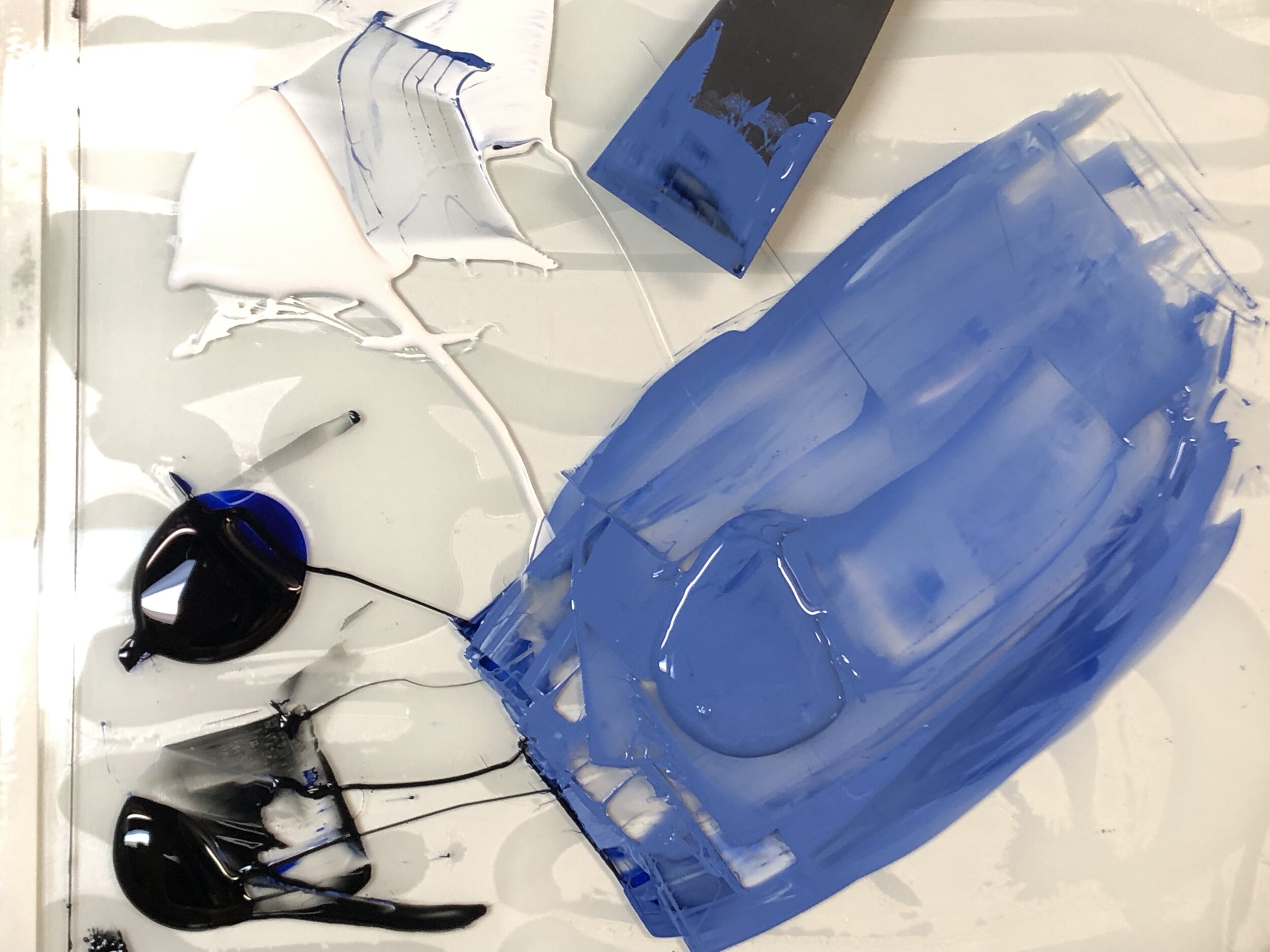

GETTING INKY

Ink for use in fine printing is another specialized component of the letterpress process. I favor oil-base ink, and have come to rely on the formulas of Hanco Ink Co (outside of Chicago, Illinois) which have very good color density and tack. For large areas of vibrant color, I use a lot of stiff opaque white added to a color base. This provides excellent ink coverage and solidity. Graphic Chemical and Hawthorn Printmaker Supplies also have very good inks.

Well, that’s a quick glimpse at some of the many folks, materials, and tools that serve the craft of printing and bookmaking. It takes a village—one that values, supports, and relies on each other. I am deeply grateful to all the people who make the stuff that makes making stuff possible.